The final tutorial in our series on gas stoichiometry will focus on an equation that combines different theories to comprehensively examine the properties of gases. However, we will soon see why this equation isn’t `ideal’.

This tutorial will explore the ideal gas law including:

- How the ideal gas law was devised and the theories it represents.

- Boyle’s Law

- Charles’ Law

- Avogadro’s Law

- Gay-Lussac’s Law

- Ideal Gas Constant

- How the ideal gas law can be used for calculations.

- Rearranging the Ideal Gas Equation.

- Using the Ideal Gas Equation.

- The Boltzmann Constant

- Problems with the ideal gas law and how these can be addressed.

- van der Waals equation.

What is the Ideal Gas Law?

The ideal gas law denotes a particular equation that can be used to calculate the variables of volume, amount, pressure and temperature when examining the properties of gases.

The gases that can be examined perfectly with the ideal gas law are referred to as ideal gases – however most real gases are rarely ideal when it comes to their properties.

Ideal gases should consist of gaseous particles (atoms or molecules) that move in a random motion; have negligible volume; have no attraction to other particles and any collision with other particles or surfaces is elastic (no net gain or loss of kinetic energy). This is according to the model within kinetic theory. However, molecules of real gases may not correspond with these assumptions and we’ll explore why this is an issue for the ideal gas law later on.

The variation in properties of gases compared to the ideal conditions is usually small and therefore the ideal gas equation can be used. However, there are some exceptions which will be discussed later on in this tutorial.

Gaseous Properties (Variables) – Definitions

Pressure: The force exerted by gaseous atoms or molecules upon impact with the walls or other surfaces of a container or vessel (e.g. cylinder) that acts as a system. This can be calculated by dividing the force exerted, by the size of the area the force is applied to, as demonstrated in the equation below using the units of Newtons per square metre (N m-2) for pressure:

Volume: The size of the system that a gas can occupy (i.e. the volume of the container or vessel).

Amount: The number of moles of a gas present in a system.

Temperature (absolute temperature): A measurement of the thermal energy that is converted into kinetic energy which leads to the movement of gaseous particles. Higher temperature leads to more kinetic energy and faster particle movement.

The Ideal Gas Equation and Units

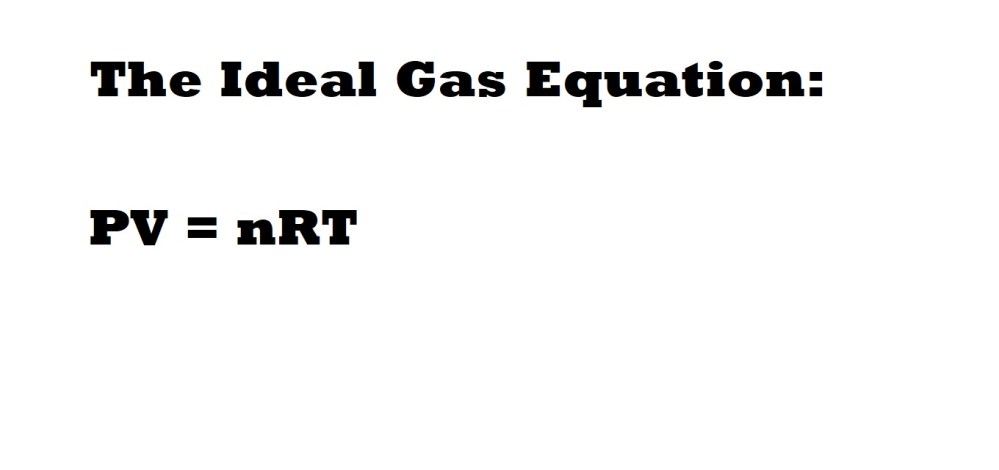

The ideal gas equation contains 4 variables: pressure; volume; amount and absolute temperature. This is accompanied by a constant value needed for calculations known as the ideal gas constant. The equation can be written as follows:

This equation demonstrates the relationship between the variables of a gas according to the ideal gas law. It shows that multiplying pressure by volume should give the same value as the value from multiplying the amount by the gas constant and absolute temperature.

However, it is important to note that the units you use can influence the process involved in the calculation; this is particularly relevant for the ideal gas constant which can differ in numerical value depending on which units you use. (It’s sometimes referred to as a ‘universal constant’ – which is kind of ironic.)

Unit Combination 1:

Unit Combination 2:

Note: I have included two possible combinations of units and each combination’s ideal gas constant. There are actually more possible unit combinations and ideal gas constants but the two I’ve included are the ones most commonly used.

The variable temperature (T) is always expressed using the absolute temperature scale which is given in kelvin (K) and amount (n) is expressed in moles (mol) – however the variables of pressure within the ideal gas law can be expressed in atmosphere (atm), pascals (Pa) or kilopascals (kPa) and volume can be expressed in metres cubed (m3) or litres (L).

*Pressure can also be expressed in N m-2 , bar, mmHg, torr and psi but the units included in the previous equations are the most commonly used for the ideal gas law.

Note: It will usually be stated in a question which unit to use to express each variable but please ask your teacher, lecturer or tutor which particular units are required for your course. I will demonstrate in this tutorial how we can convert from one unit to another which could be required to answer a question with the correct units.

I will explain the ideal gas constant (including that weird looking arrangement of units in the second combination) in further detail soon – but let’s first examine the different laws that are represented in the ideal gas law.

The Laws within the Ideal Gas Law

Boyle’s Law

Source of Image: http://webfis.df.ibilce.unesp.br/tunel/2page/galeria.html, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1436269)

Note: This law was named after the Anglo – Irish scientist and philosopher Robert Boyle who did make a crucial contribution to science by endorsing and propagating the provision of experimental evidence for theories in the field of chemistry– something that has become a fundamental feature today. However, there is evidence that suggests that the experiments that initially prompted the proposal of ‘Boyle’s law’ were actually conducted by English scientist Richard Townley and English physician Henry Power [1] .

This law was devised following the examination of the properties of volume and pressure in gases of a fixed amount that were maintained in a closed system at a constant temperature.

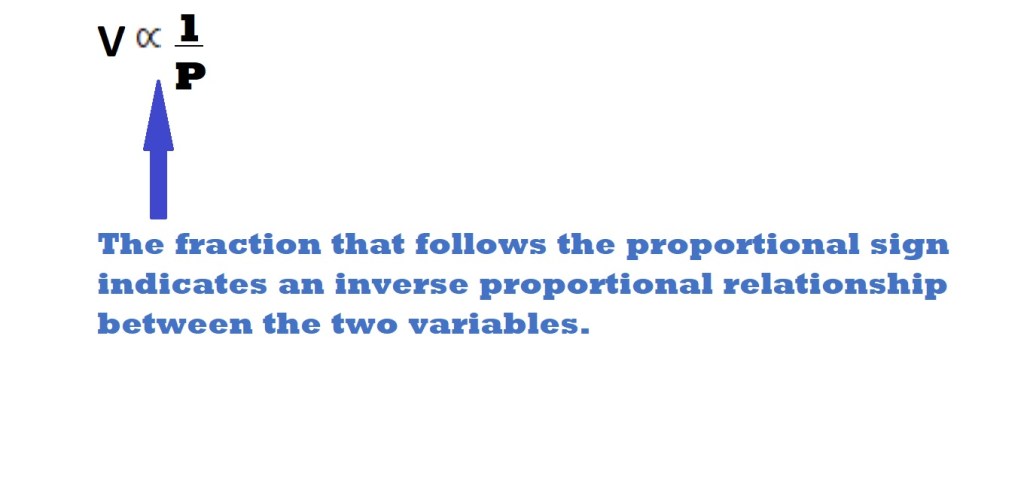

The main point this law states is that there is an inverse proportional relationship between the volume and pressure of a fixed amount of a gas at a constant temperature. This means that a change in volume by a certain magnitude (e.g. doubling) will be accompanied by a change in pressure by the same magnitude but with the opposite effect (e.g. halved). This means that if volume decreases – pressure increases and vice- versa. This is illustrated with the following:

This relationship accounts for the increase in pressure that occurs with a decrease in volume as atoms or molecules are more likely to exert a force on the sides or surfaces of a container or vessel upon more frequent contact if the space available is smaller. It also accounts for the decrease in pressure if volume increases as there is more space for the atoms or molecules to move and therefore will make contact with sides or surfaces less frequently.

This relationship means that the value that results from the multiplication of the values for pressure and volume will remain constant. This is signified in the equations below:

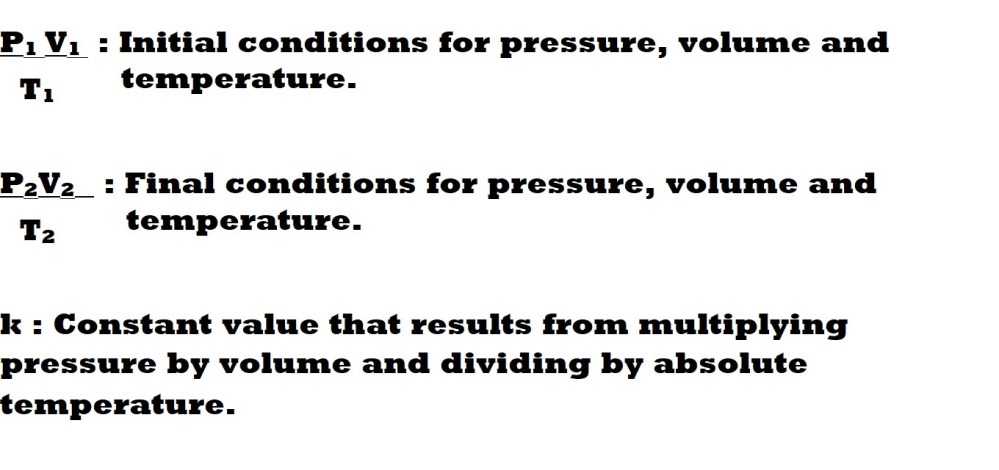

P1V1 : Initial conditions for pressure and volume prior to changes.

P2V2 : Final conditions for pressure and volume following changes.

k: Constant value that results from multiplying the pressure value by the volume value in each set of conditions.

The equations above illustrate that due to the inverse proportional relationship between volume and pressure – and providing that temperature is constant and the amount is fixed – the value that results from multiplying the initial pressure by the initial volume will be the same as the value that results from multiplying the final pressure value by the final volume value following changes; this value is known as a constant (k).

Let’s look at an example:

Example:

Initial Conditions:

P1: 34 kPa

V1: 2.3m3

Final Conditions

P2 : 17 kPa

V2: 4.6 m3

The pressure has halved from 34 kPa to 17 kPa whereas the volume has doubled from 2.3 m3 to 4.6 m3. This could occur if a piston is decompressed and gaseous atoms or molecules have a greater volume to occupy and therefore make contact with the sides of the container less frequently leading to a decrease in pressure.

The inverse proportional changes in volume and pressure means that the constant value that results from multiplying the variables is 78.2 for both sets of conditions.

Physiological Example: Breathing

We demonstrate Boyle’s law everyday of our lives when we breath (technically known as pulmonary ventilation). When we inhale air our lungs expand leading to an increase in volume which leads to a decrease in pressure. This means that the pressure within our lungs is lower than the pressure outside the lungs, therefore air flows into the lungs as air moves from a region of high pressure to a region of low pressure. When we exhale our lungs contract leading to a decrease in volume and an increase in pressure meaning air in the lungs has a higher pressure than air outside the lungs which leads to air moving out of the lungs from a region of high pressure to a region of low pressure.

Charles’ Law

Figure 2: Illustration of the beginning of Jacque Charles’ and Nicolas-Louis Robert’s flight in a hydrogen-filled balloon in Paris 1783.

Source of Image: By Antoine Louis François Sergent dit Sergent-Marceau – United States Library of Congress LC-DIG-ppmsca-02284 (digital file from original drawing), uncompressed archival TIFF version (52 MiB), color level (pick white point, adjust black & white levels), and converted to JPEG (quality level 88) with the GIMP 2.6.1, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=228583

Charles’ law (credited to French scientist and balloon enthusiast Jacques Charles by fellow French scientist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac who published the law) examines the properties of volume and temperature in a gas that’s maintained at a constant pressure and fixed amount in a closed system.

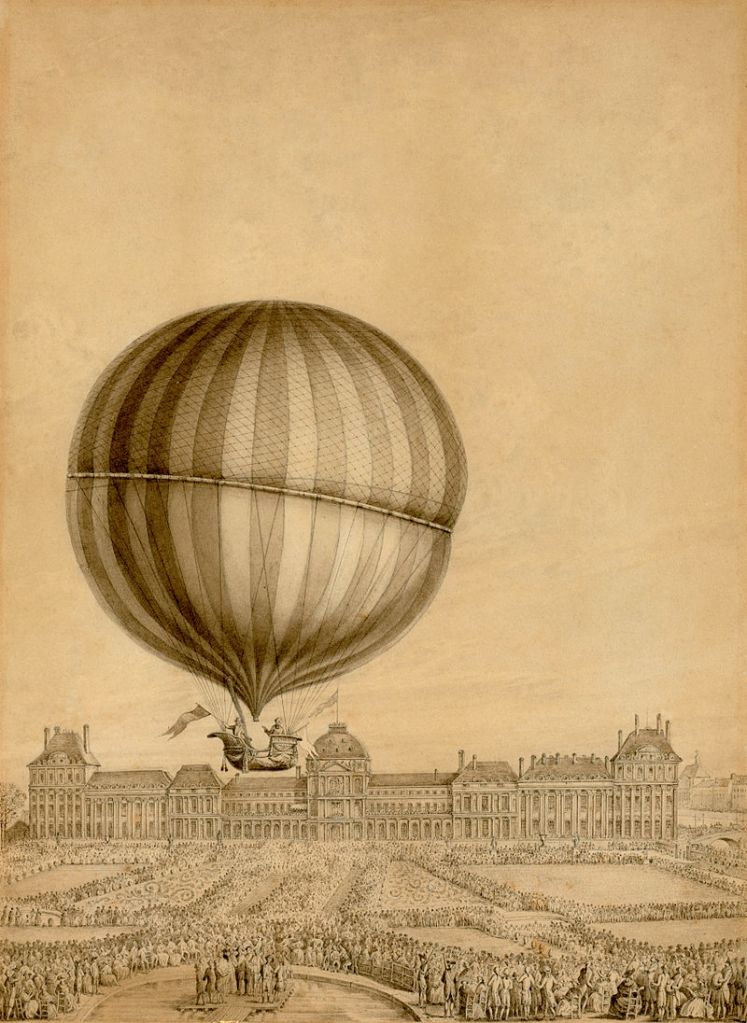

The law states that there is a direct proportional relationship between the volume and temperature of a fixed amount of a gas as long as pressure remains constant.

This means that a change in temperature will lead to change in volume and the magnitude (size) and effect of the change will be the same for both variables. If temperature increases – volume increases and vice-versa. If the temperature of a gas triples – the volume of the gas triples.

The law accounts for an increase in temperature causing a gas to expand thereby increasing volume. This is due to more space existing between atoms or molecules as they move more rapidly as they have more kinetic energy as a result of the energy transfer of thermal energy to kinetic energy. This means the gaseous atoms or molecules can move further apart and occupy more space.

Alternatively, it also accounts for a decrease in temperature leading to the contraction of a gas and therefore a decrease in volume. This is due to less space existing between atoms or molecules as they have less average kinetic energy, move at a slower rate and become closer to one another thereby occupying less space.

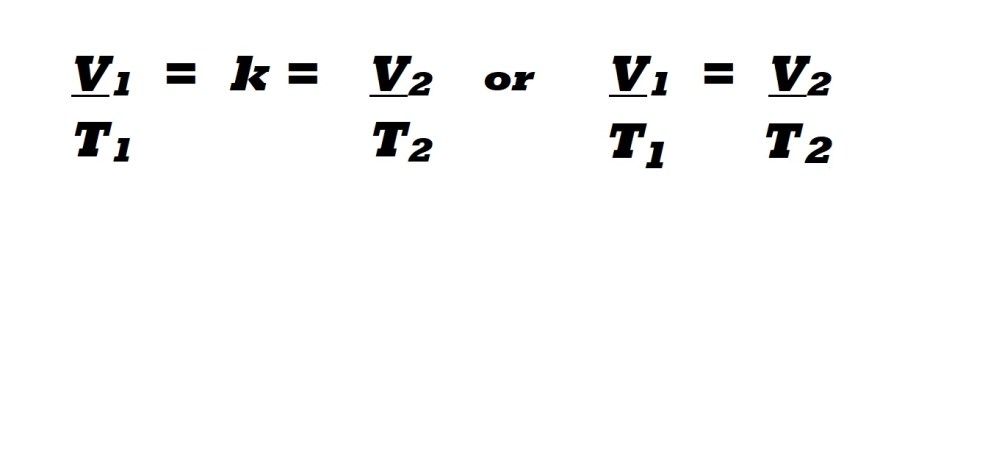

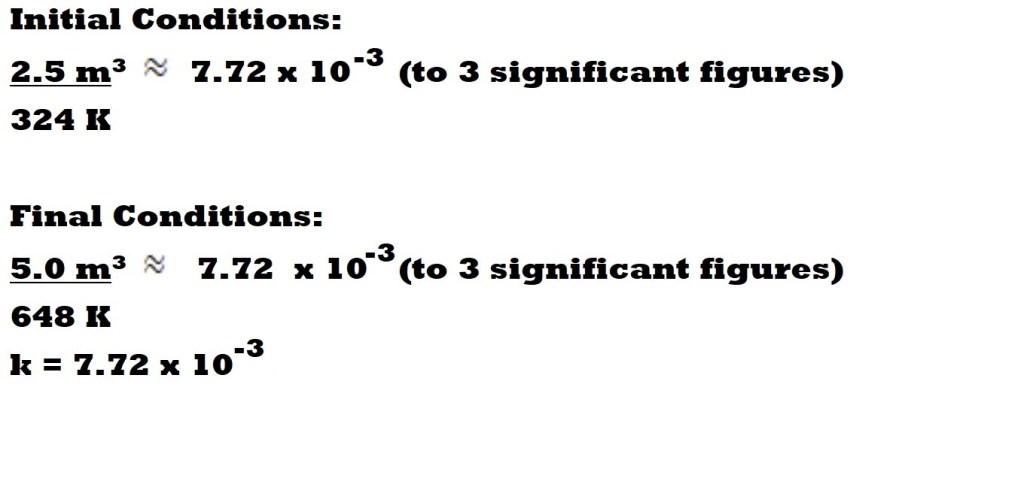

This direct proportional relationship between the volume and temperature of a gas means that dividing the volume of a gas by the temperature will result in a constant value (k). This is summarised by the following equation which denotes the volume and temperature prior to changes and after changes:

V1 : Initial conditions for volume and temperature prior to changes. T1

V2 : Final conditions for volume and temperature following changes. T2

k: Constant value that results from dividing the volume value by the temperature value in each set of conditions.

Example:

V1: 2.5 m3

T1: 324 K

V2 : 5.0 m3

T2: 648 K

The volume has doubled as a result of the doubling of the temperature.

Note: I have included the answer for the previous calculations in standard form (also known as scientific notation) as this is the conventional way of expressing either very large or very small values.

The direct proportional relationship between volume and temperature means a constant value of 7.72 x 10-3 (to 3 significant figures) results from dividing the volume of a gas by the temperature in both sets of conditions.

However, the expansion of a gas in response to an increase in temperature depends on the gas being situated in a suitable vessel. If a gas is within a sealed container it will not be able to expand due to being restricted by the rigid walls of the container.

For example, if a gas was situated in a sealed solid beaker the gas will not be able to expand as much as it would be able to in an elastic balloon.

Avogadro’s Law

Figure 3: Illustration of Italian scientist Amedeo Carlo Avogadro (1776 – 1856).

Source of Image: C. Sentier, executed in Torino at Litografia Doyen in 1856. – Edgar Fahs Smith collection, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons ,https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4075388

Avogadro’s Law (named after the Italian physicist Amedeo Carlo Avogadro) examines the properties of the amount and volume of a gas.

Avogadro carried out experiments involving various gases in systems at different temperatures and pressures. His work proved that equal volumes of different gases will contain the same number of molecules providing temperature and pressure remains constant.

Alternatively, this can expressed by stating that the volume of a gas is directly proportional to its amount if temperature and pressure remains constant. This means that any change in volume will lead to a change in amount by the same magnitude and the same effect. For instance, if the volume in which a gas can occupy quadruples this will be accompanied by the quadrupling of the amount of the gas present.

Reminder: If you are given the amount of a substance in particles such as molecules, atoms or ions and you need to convert to moles you must divide by Avogadro’s constant which is 6.02 x 1023 .

There is a way to include the number of particles of a gaseous substance rather than moles in a modified version of the ideal gas equation which we will explore later in this tutorial.

This direct proportional relationship accounts for the potential for more moles of a gas to occupy a larger volume and for fewer moles of a gas to occupy a smaller volume.

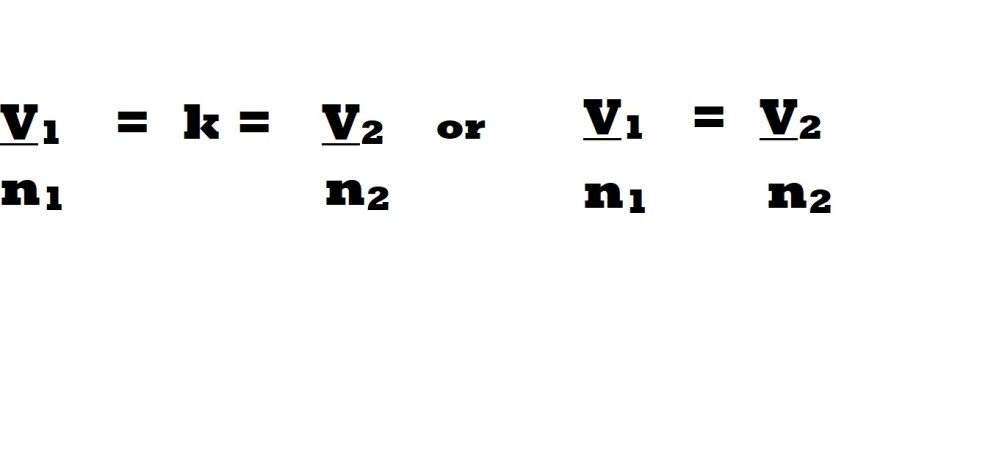

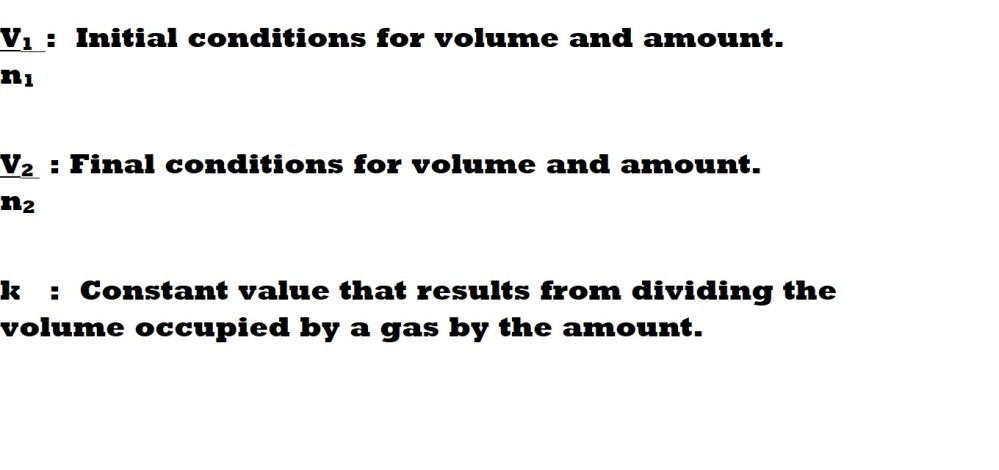

The direct proportional relationship between volume and the amount of a gas according to Avogadro’s Law means that the value resulting from dividing the volume of a gas (V) by its amount (n) will result in a constant value. This is summarised by the following equation which represents the volume and amount of a gas prior to changes and the values of the variables following changes:

Avogadro’s law is demonstrated by the specific volume of 1 mole of a gas in the conditions of standard temperature and pressure (STP) or room temperature and pressure (RTP). Please refer to the tutorials entitled: ‘Gas Stoichiometry Part 1 – STP’ and ‘Gas Stoichiometry Part 2 – RTP’ for more information on both sets of conditions and calculations involving these conditions.

However, we will return to STP later on in this tutorial as this set of conditions can be used to demonstrate a crucial part of the ideal gas law.

Gay-Lussac’s Law

Figure 4: Illustration of French chemist and physicist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1778 – 1850).

Source of Image: https://wellcomeimages.org/indexplus/obf_images/38/3f/01c52e04f378927824c5da2e0b75.jpg Gallery: https://wellcomeimages.org/indexplus/image/L0005556.htmlWellcome Collection gallery (2018-04-01): https://wellcomecollection.org/works/ys3ud22p CC-BY-4.0, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35869838 (No changes have been made to the original image.)

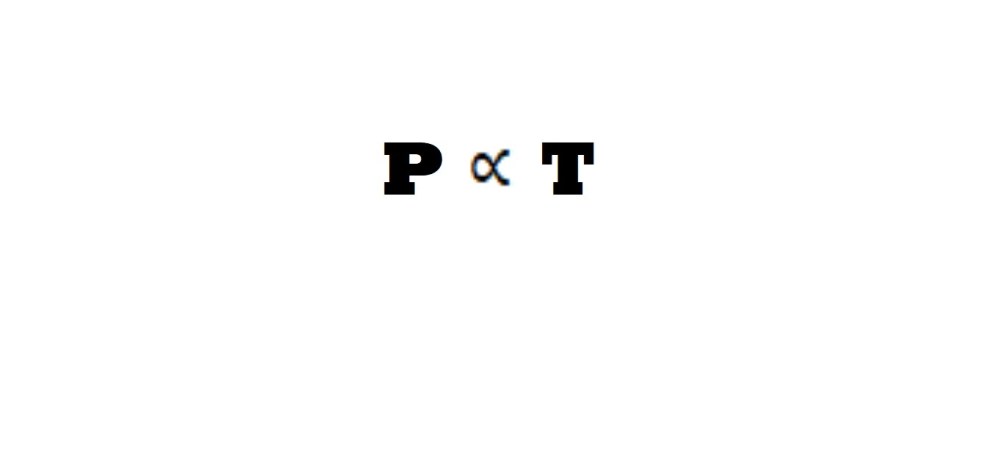

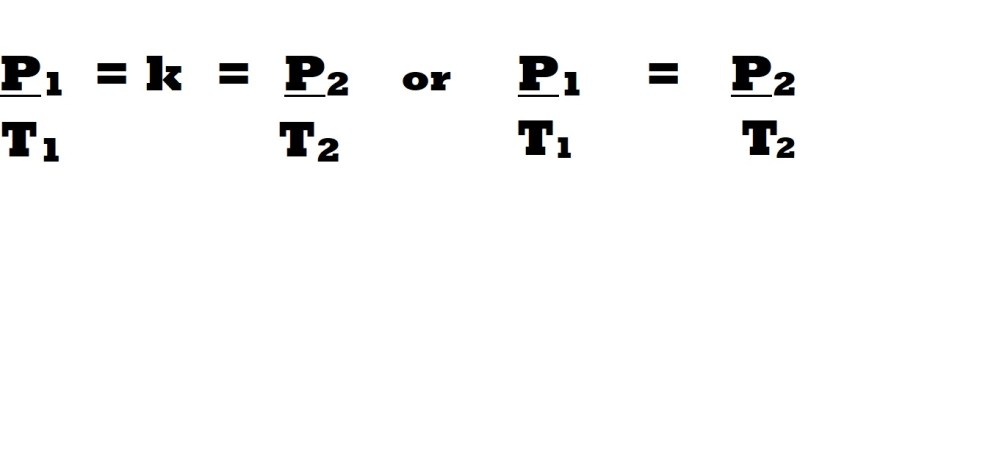

This law (named after French scientist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac) examines the variables of pressure and temperature when amount and volume are constant.

The law states that at a constant amount within a constant volume, there is a direct proportional relationship between pressure and absolute temperature.

This direct proportional relationship means that any change in pressure will be accompanied by a change in temperature by the same magnitude with the same effect. Therefore, an increase in temperature leads to an increase in pressure and vice – versa. This means that the division of the value for pressure by the temperature will lead to a constant value (k). This is demonstrated in the equations below for the conditions of pressure and temperature prior to changes and following changes:

This direct proportional relationship accounts for the increase in average kinetic energy in atoms or molecules that results from the increase in thermal energy from the increase in temperature. This leads to an increase in pressure as the gaseous atoms or molecules move at a faster rate meaning they make contact more frequently with the sides or surfaces of a container or vessel. Conversely, it also accounts for the decrease in absolute temperature leading to a decrease in pressure as atoms or molecules move at a slower rate and therefore make less frequent contact with surfaces due to lower average kinetic energy.

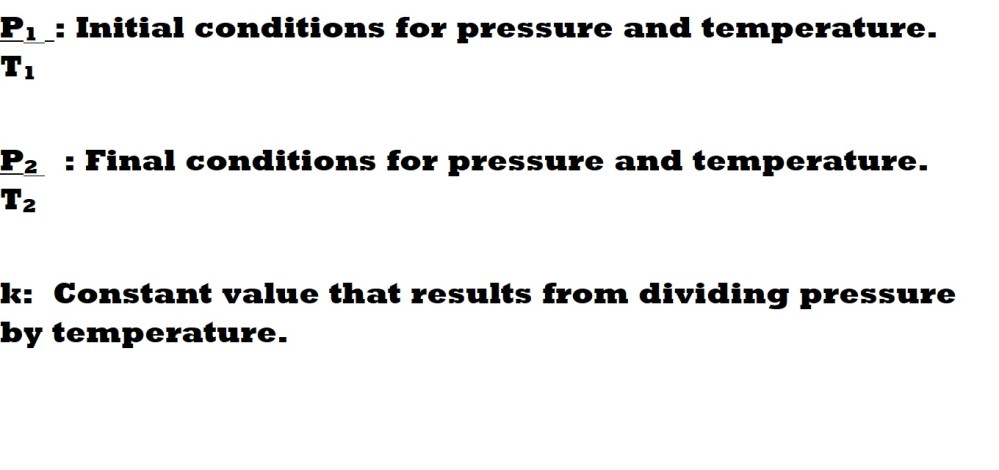

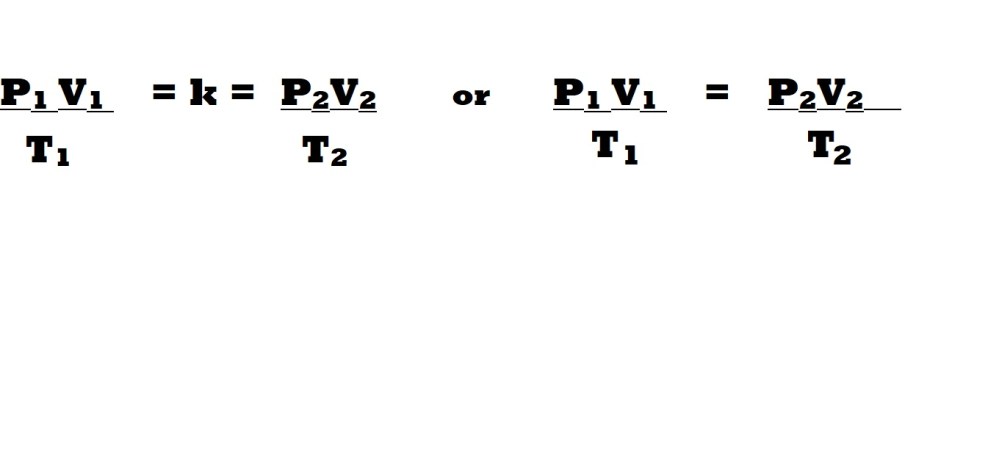

Combined Gas Law

The combined gas law was devised to combine Boyle’s law, Charles’ law and Gay-Lussac’s law and is represented by the following equation:

This equation states that the value resulting from multiplying the pressure by volume and dividing by absolute temperature will result in a constant (k) if the amount of the gas remains constant.

This equation represents the relationships between three of the variables within the behaviour of ideal gases – however it does not comprehensively account mathematically for the constants established by the three laws, nor does it account for possible variability in amount and its effect on volume ( i.e. it doesn’t include Avogadro’s law).

The representation of the constants within all the laws was addressed by the establishment of the ideal gas constant.

What is the Ideal Gas Constant?

The ideal gas constant (R) was established via the experimental measurement of the volume of gas released or used up during a chemical reaction. It was found that equal volumes of ideal gases at a certain temperature and pressure contain an equal number of moles.

Sounds familiar? That’s because this is the central rule behind mole calculations of gases at STP and RTP and to understand how the ideal gas constant was established we have to go back to STP.

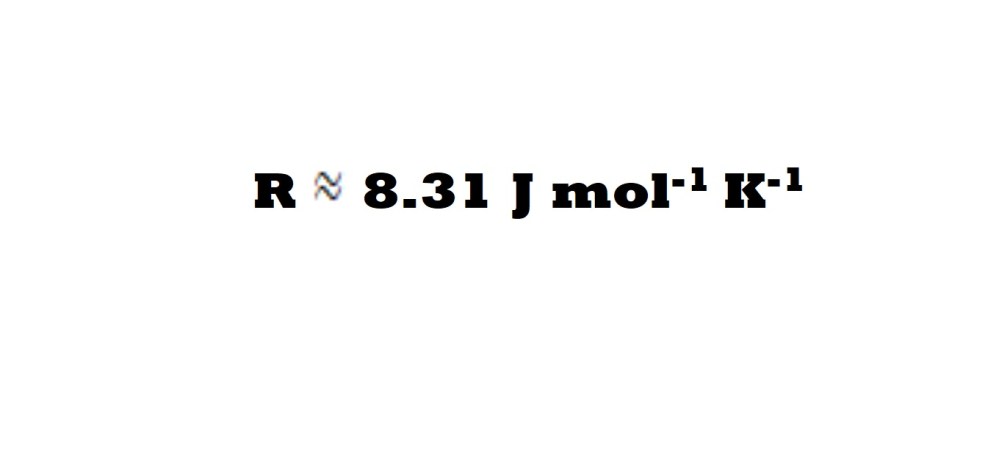

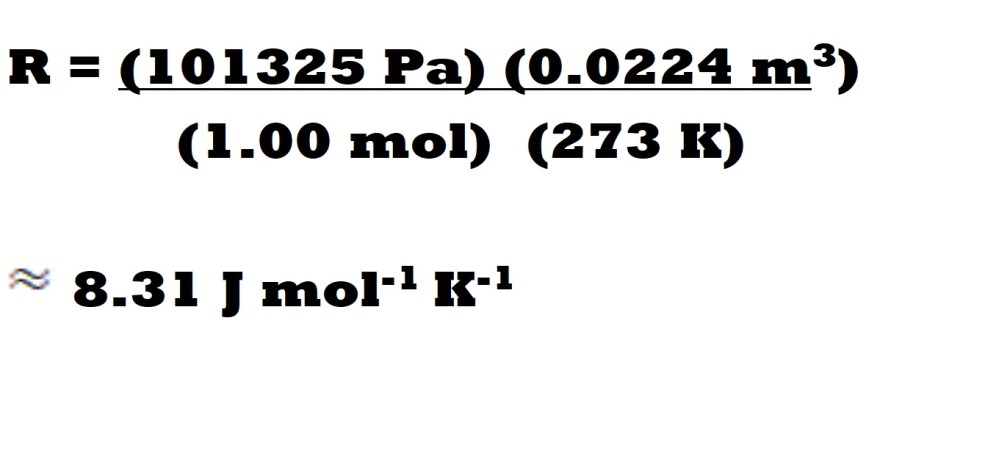

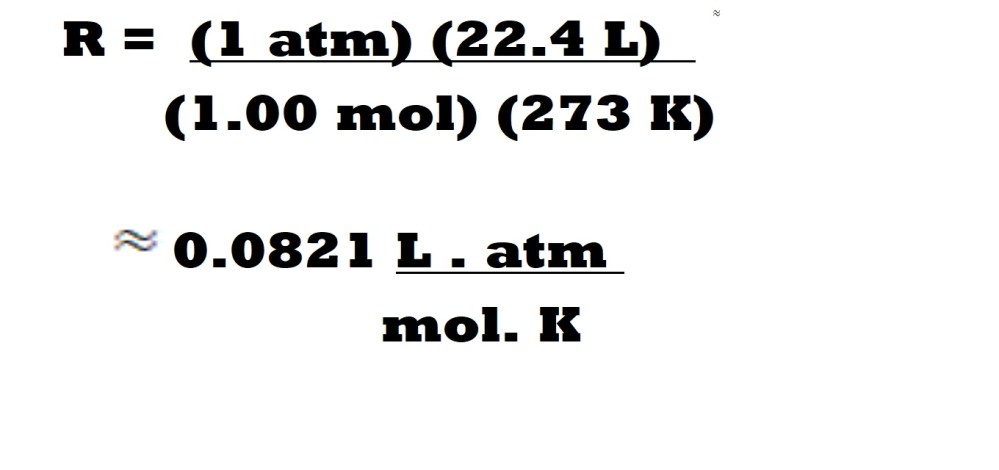

Standard temperature and pressure (STP) is a set of conditions in which 1 mole of a gas in a system at 273K (0oC) with a pressure of 101325 Pa (1 atm) occupies a volume of 0.0224 m3 (22.4 L).

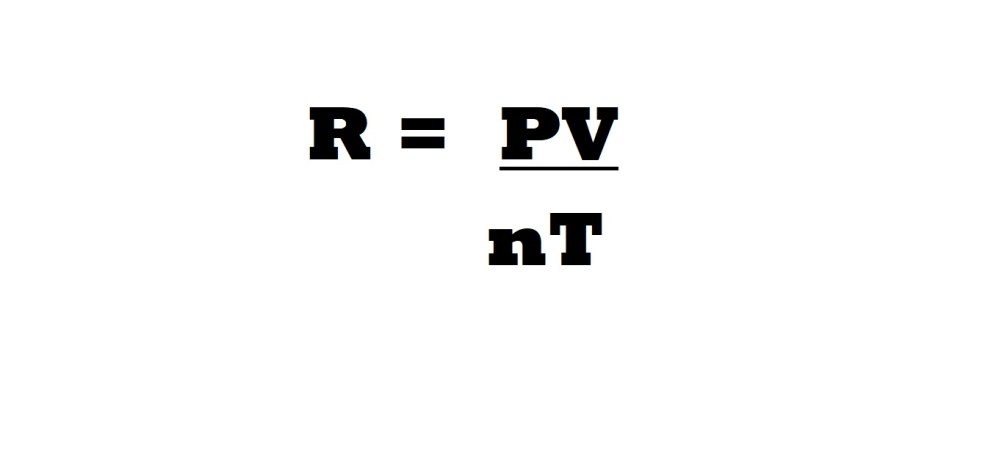

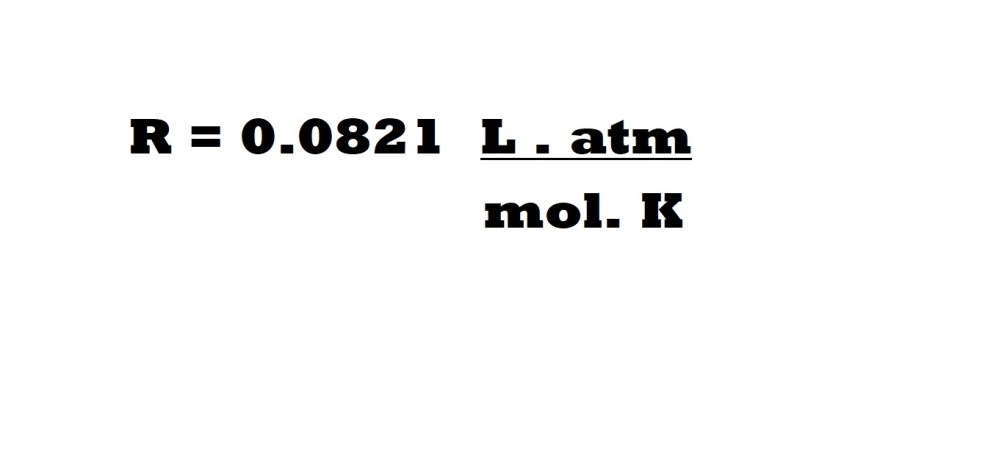

The aforementioned values are crucial because if you convert them into appropriate units and plug them into the equation below you will calculate the ideal gas constant.

However, the numerical value and units of the ideal gas constant can differ depending on which combination of units you are going to use.

Below are the two most commonly used ideal gas constants (rounded to 3 significant figures) :

This ideal gas constant should be used when expressing pressure in pascals (Pa), volume in metres cubed (m3), amount in moles (mol) and absolute temperature in Kelvin (K). We can prove this ideal gas constant mathematically with the values at STP as follows:

Note: Joules (J) represents the units of Pa for pressure and m3 for volume due to the following relationship:

Pa m3 = N m-2 m3 = N m = J

1 Pa = 1 N m– 2

1 N m = 1 J

A second possible combination of units for an ideal gas constant is illustrated below:

This ideal gas constant should be used when expressing volume in litres, pressure in atmosphere (atm), amount in moles (mol) and absolute temperature in Kelvin (K). We can prove this ideal gas constant mathematically with the values at STP as follows:

Reminder: 1 atmosphere (1 atm) is the pressure of air at sea level and is equivalent to 101.325 kPa or 101325 Pa ( 101 kPa or 1.01 x 105 Pa to 3 significant figures).

The second option – with that weird looking fraction of units – allows for the cancellation of units so that we only include the unit we want for our answer. I’ll demonstrate how to do this shortly – but first let’s look at how to rearrange the ideal gas equation.

Using the Ideal Gas Law

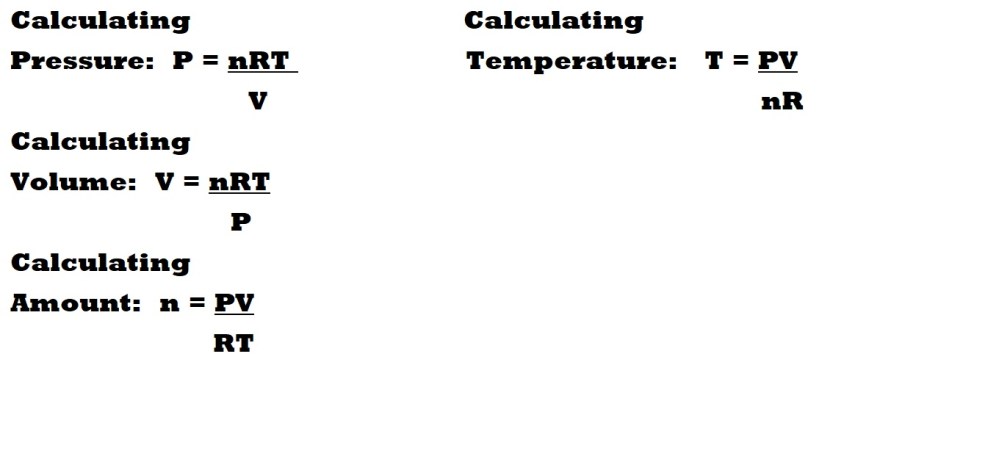

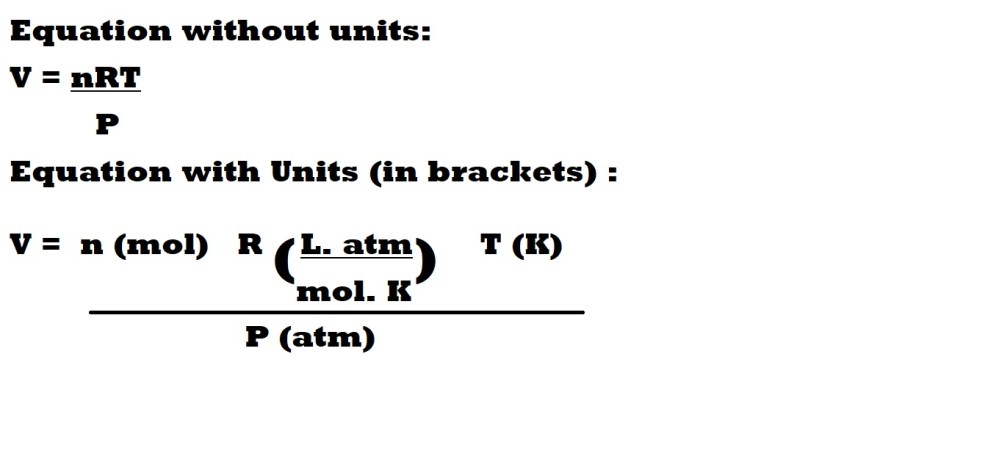

Rearranging the Ideal Gas Equation

When working out the value of a particular variable, we should rearrange the ideal gas equation to ensure the subject of the equation is the variable we are examining.

If you Know 3 the 4th will be Revealed

When using the ideal gas equation one of the most important things to remember is that once you know the values for three of the variables within the equation you can calculate a fourth variable.

In an exam or test you will usually be provided with information within a question about three of the variables. The information will either give you values you need with the correct units or an equivalent value with a different unit which you have to convert.

Let’s now look at some questions which will involve converting values to ensure the appropriate units are included.

Questions and Calculations

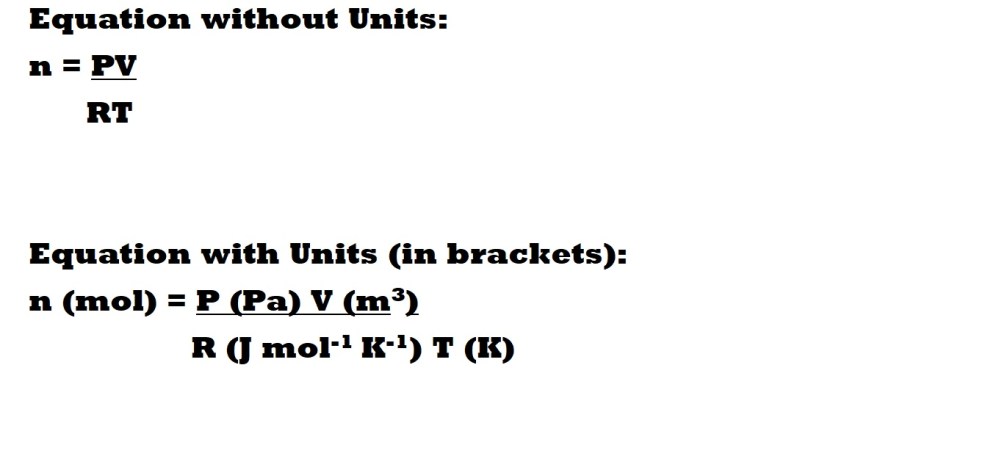

Note: We will go through one question for each of the two most common combinations of units used for the ideal gas equation. Please check with your tutor, teacher or lecturer which combination of units is required for your course.

Question 1: A sealed container contains 40.0 dm3 of oxygen gas (O2) at a pressure of 110 kPa and a temperature of 38.0 oC. How many moles of oxygen are present in the container?

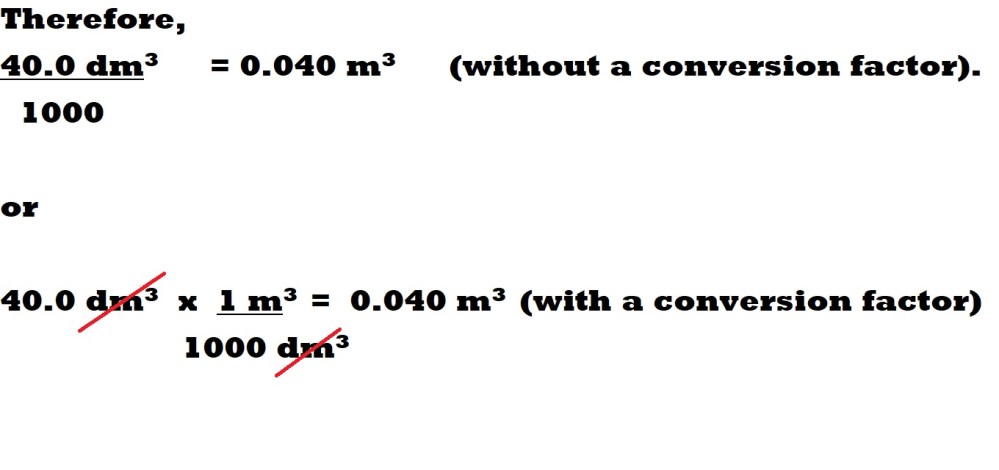

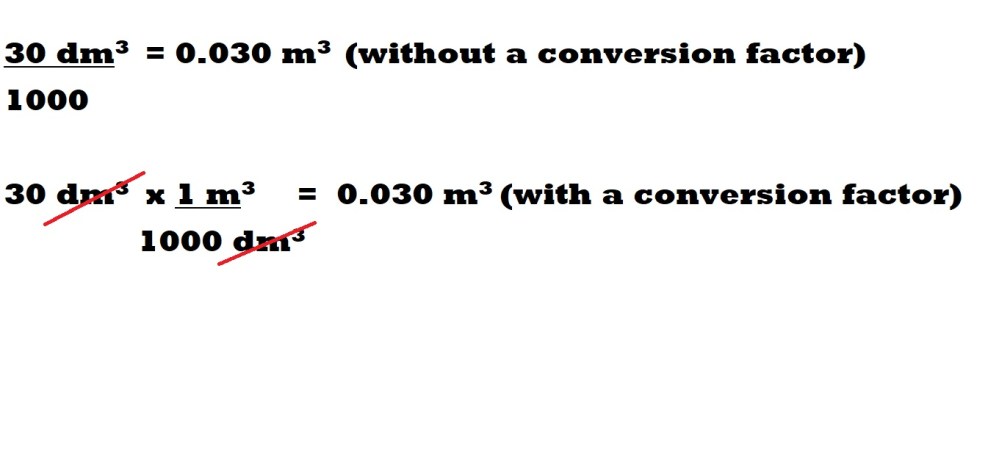

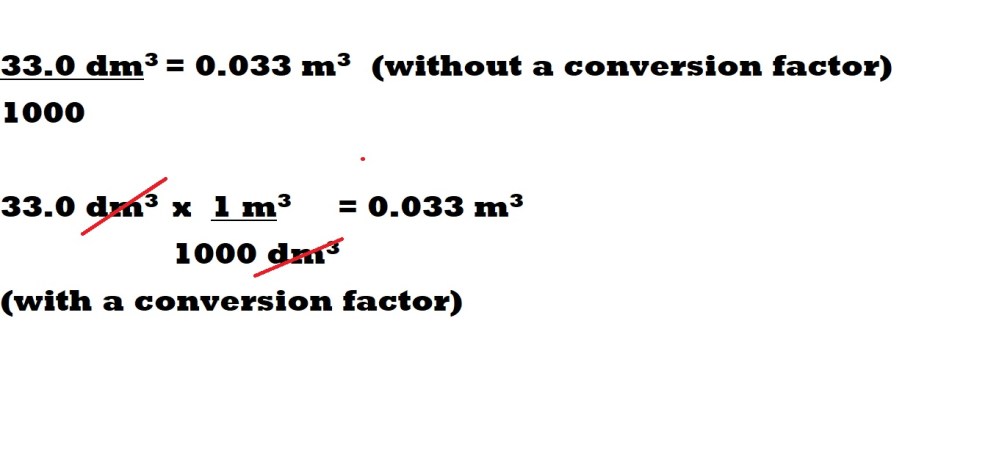

Step 1: Convert the volume from decimetres cubed (dm3) into the appropriate units of metres cubed (m3).

To convert from dm3 to m3 we must divide by 1000.

We can do this with a conversion factor (a fraction consisting of two equivalent values that allows for the cancellation of units we don’t want for our answer) or without a conversion factor.

Note: Please check with your tutor, teacher or lecturer whether you need to use conversion factors for your course.

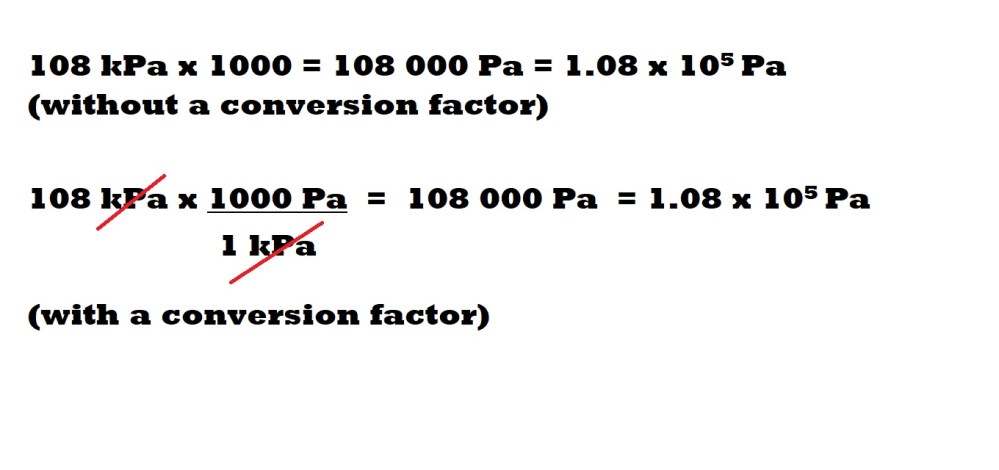

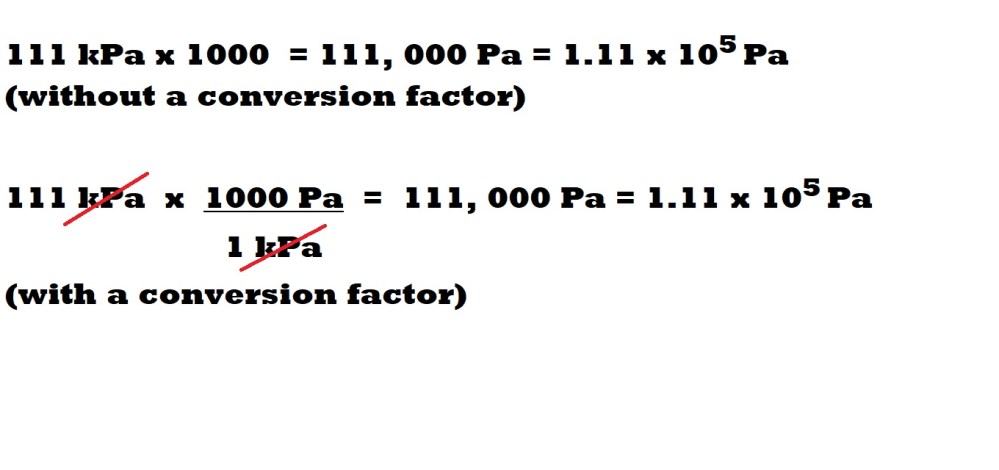

Step 2: Convert the pressure from kilopascals (kPa) to pascals (Pa)

There are 1000 pascals (Pa) in 1 kilopascal (kPa) therefore to convert from kilopascals to pascals we need to multiply by 1000.

This can also be done with a conversion factor and without a conversion factor:

Note: I have included the answers in standard form (scientific notation) as you may have to show that you can convert large numbers or small numbers into this form.

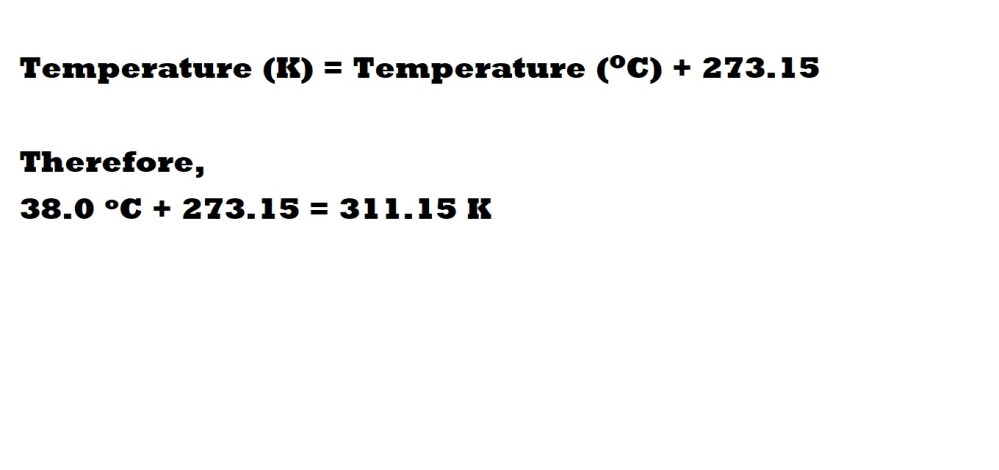

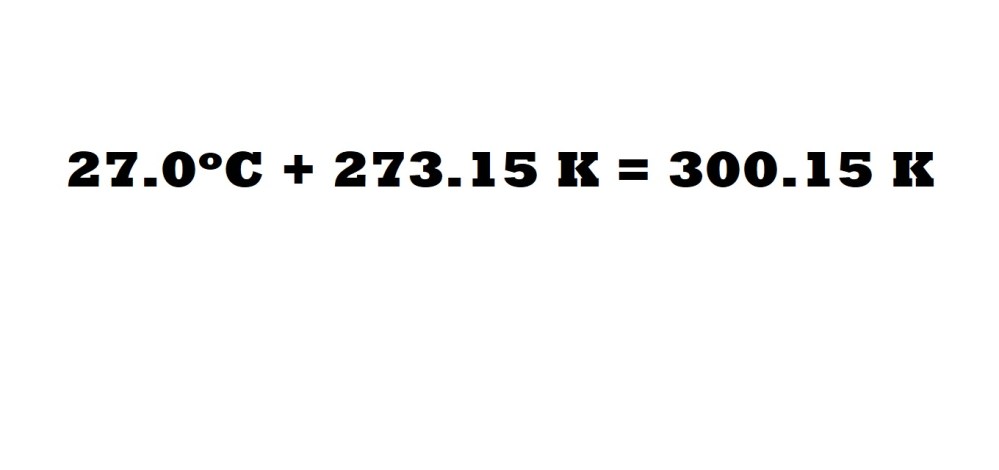

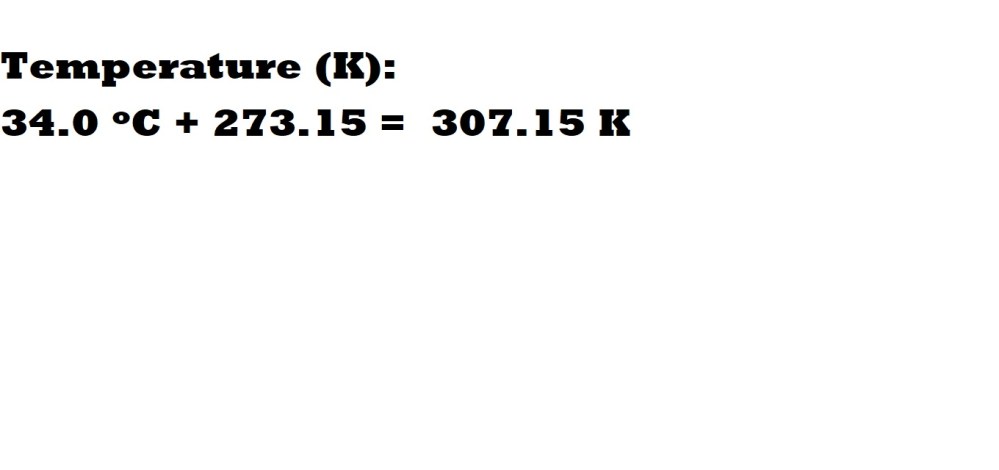

Step 3: Convert the temperature from Celsius (oC) to Kelvin (K).

To convert Celsius to Kelvin we must remember that a value of 0oC is 273.15 K – therefore to convert from Celsius to Kelvin we must add 273.15 to the temperature we have in Celsius. This can be summarised with the following equation:

Note: I have included the absolute temperature value in Kelvin to 2 decimal places to ensure consistency within the calculation – however you may be asked to assume a value of 273 K for 0OC.

Step 4: Insert the values for volume, pressure and temperature into the rearranged ideal gas equation with the ideal gas constant and calculate the amount in moles.

We now have the values for 3 variables with the correct units and therefore can insert them into the rearranged equation with the ideal gas constant and calculate the amount in moles.

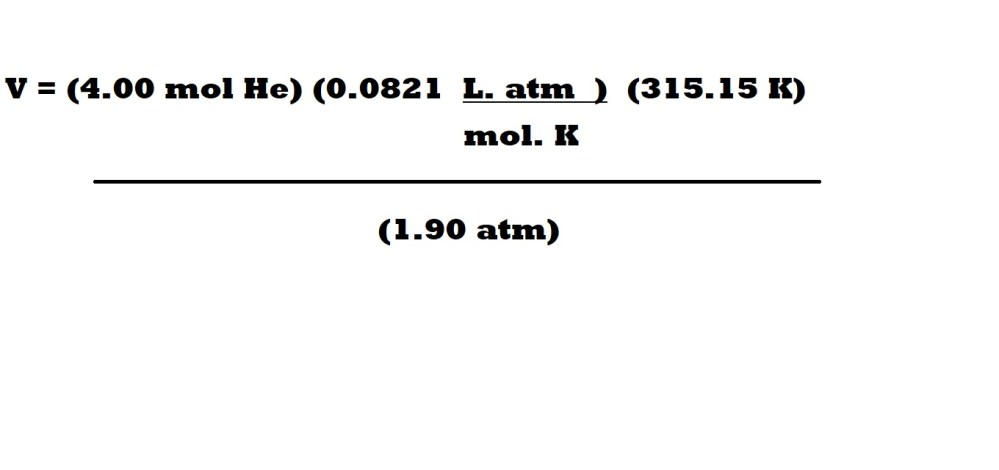

Question 2: What is the volume in litres (L) of 4.00 moles of helium (He) at a pressure of 1.90 atm and a temperature of 42.0 oC?

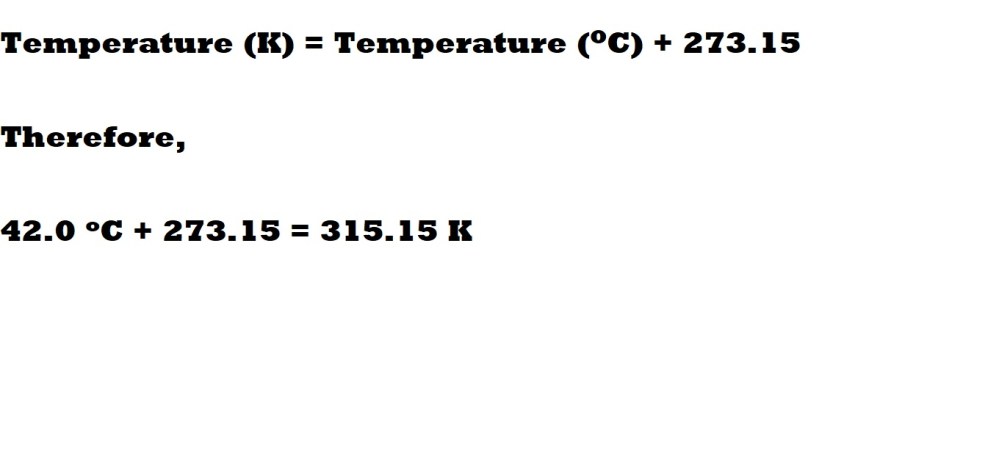

Step 1: Convert the temperature from Celsius (oC) to Kelvin (K).

To convert Celsius to Kelvin we must remember that a value of 0oC is 273.15 K – therefore to convert from Celsius to Kelvin we must add 273.15 to the temperature we have in Celsius. This can be summarised with the following equation:

Step 2: Insert the values for volume, amount, pressure and the ideal gas constant into the rearranged ideal gas equation.

We now have the values for 3 variables with the correct units so we can now insert these values with the ideal gas constant into our rearranged equation.

Step 3: Cancel out the units we don’t want for our answer and calculate the final answer with a suitable number of significant figures.

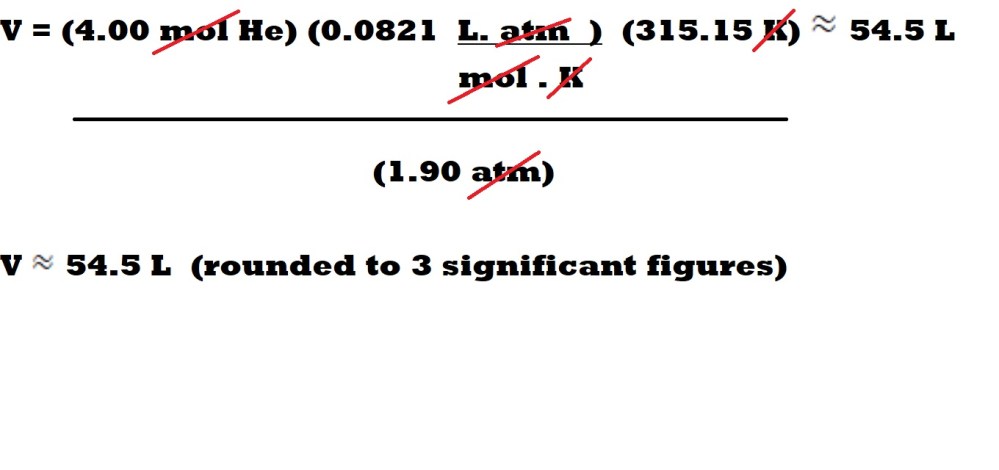

What about Density?

Density is the mass of a substance per volume and can usually be calculated with the following equations:

Density is another variable that could be considered when examining the behaviour of gases – but it is not conventionally included in the ideal gas law.

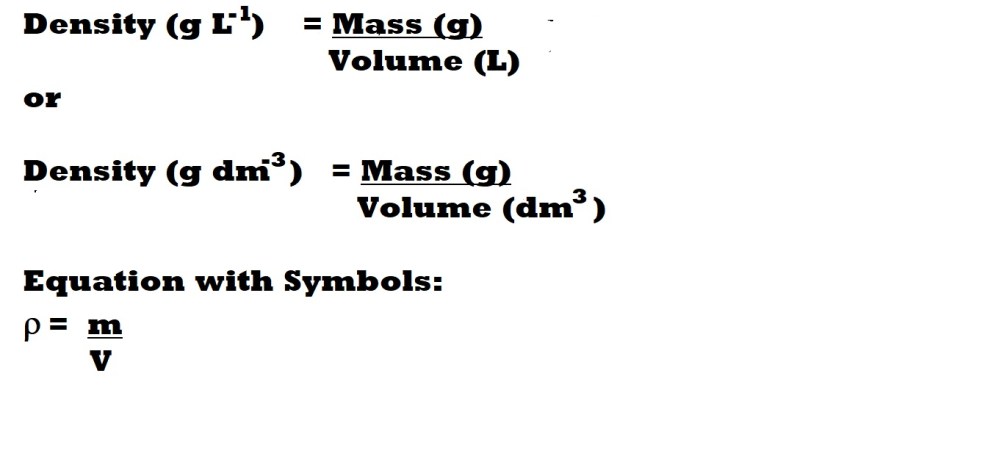

However, there is a way of changing the equation to account for the density of a gas.

The equation above is a modified version of the ideal gas equation in which we have replaced the variable of volume with density and the amount in moles with molar mass.

Reminder: Molar mass is the mass of one mole of a substance and is conventionally expressed in g mol-1.

Let’s look at how we can use this modified version of the ideal gas equation to calculate the density of a gas.

Question: What is the density in g L-1 of carbon dioxide gas (CO2) at 1.40 atm and 29.0 oC?

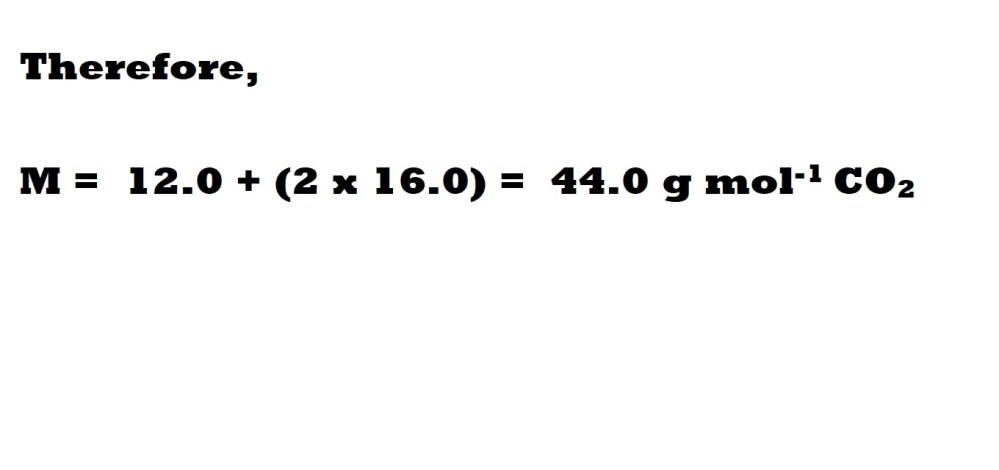

Step 1: Find the molar mass of carbon dioxide.

We have only been given information about two variables within the question and we need to know the values for 3 variables to calculate a fourth.

The 3rd variable we need is the molar mass and we can calculate this ourselves.

A molecule of carbon dioxide contains one carbon atom and two oxygen atoms – therefore we need to include the relative atomic mass of 1 carbon atom and multiply the relative atomic mass of oxygen by 2 to account for 2 oxygen atoms.

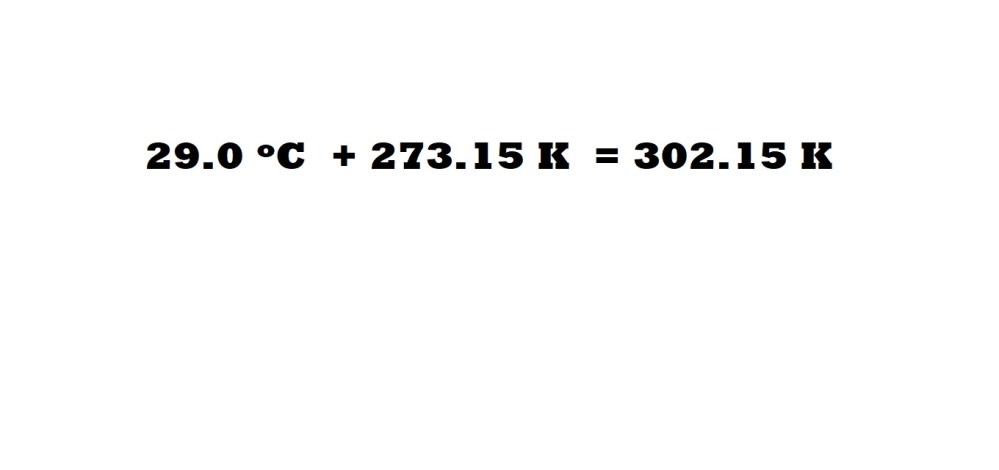

Step 2: Convert the temperature from Celsius to Kelvin.

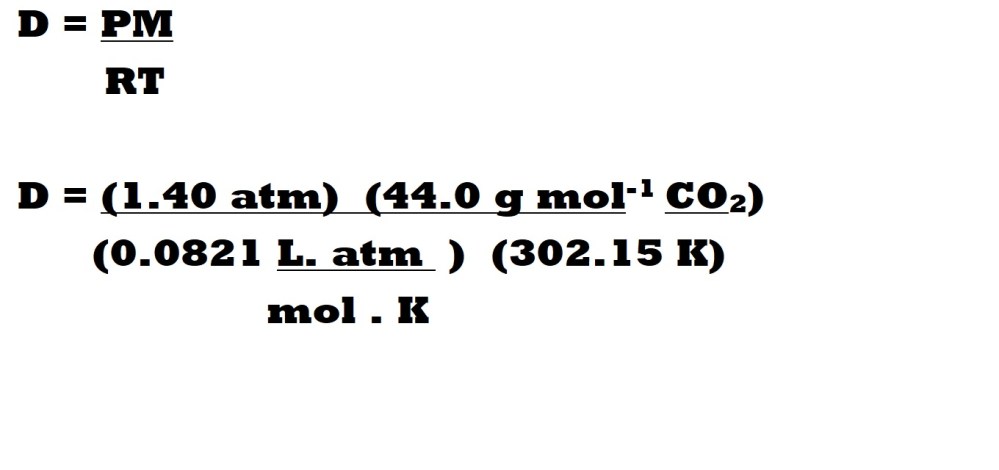

Step 3: Insert the values for pressure, temperature, molar mass and the ideal gas constant into the modified ideal gas equation with the relevant units.

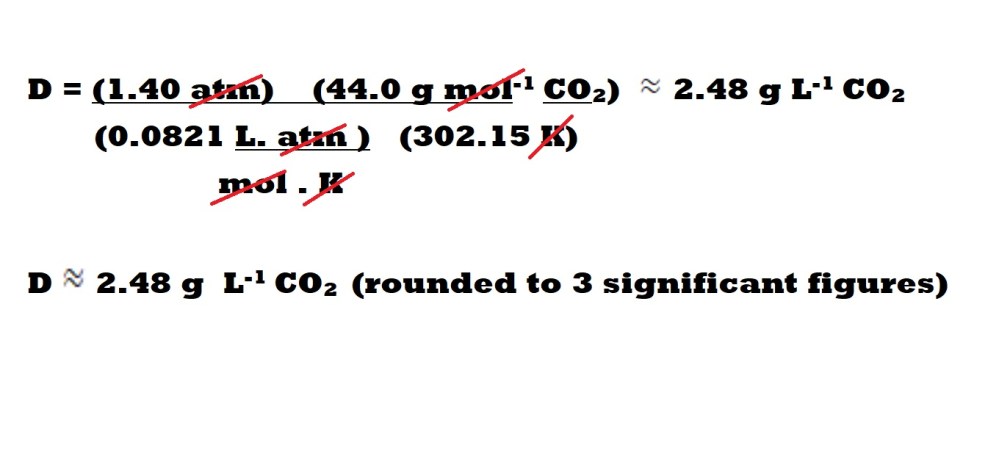

Step 4: Cancel out the units we don’t want for our answer and calculate the final answer with a suitable number of significant figures.

What about Mass?

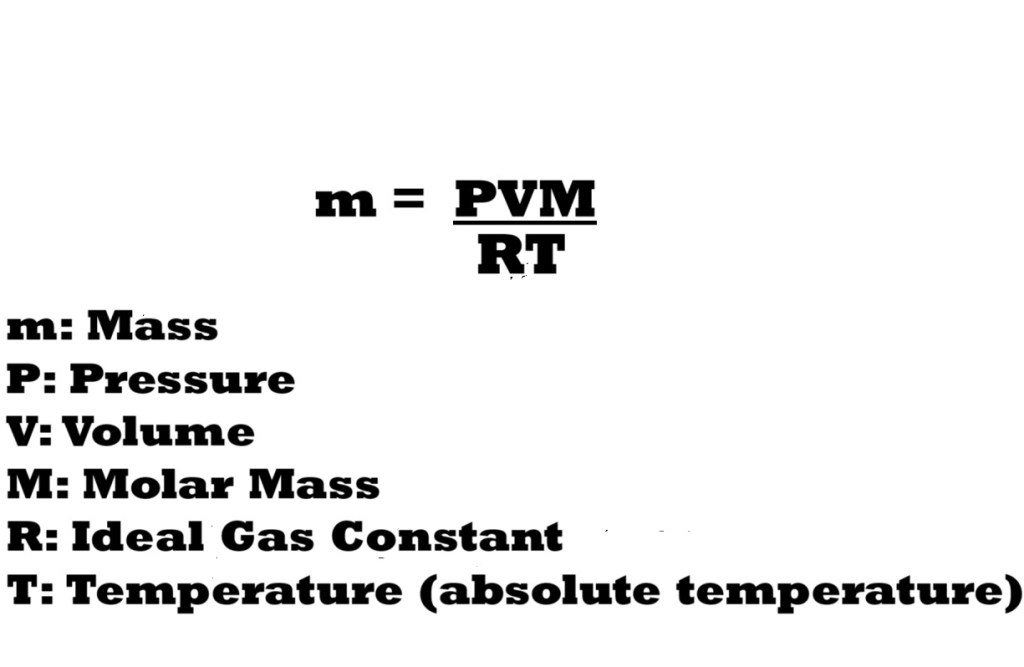

The mass of a sample of a gas (conventionally expressed in grams) can also be calculated with a modified version of the ideal gas equation.

The variable that provides the link between the ideal gas equation and the calculation of the mass of a gas sample, is moles. The reason lies in the fact that to calculate moles, we must divide mass by the molar mass as seen in the familiar equation below:

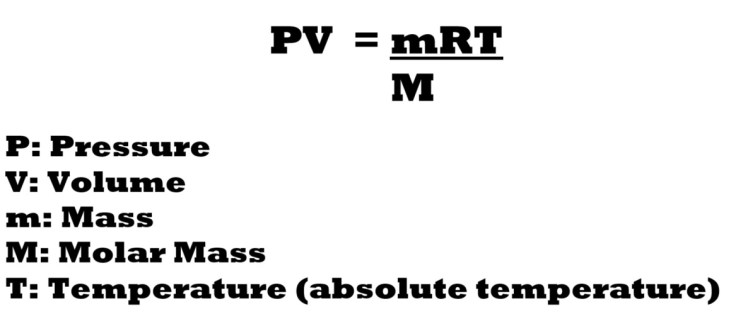

If we take out n – the amount in moles – in the ideal gas equation and replace it with a lower-case m for mass in the numerator and a capital M for molar mass in the denominator, we get the modified version of the ideal gas equation below:

Now that mass has been included in the ideal gas equation, we can now rearrange the equation to make mass the subject.

This indicates that to calculate the mass of a gas sample in a system, we must multiply the pressure by the volume and the molar mass, before dividing by the ideal gas constant multiplied by the temperature.

Let’s now look at a question that at first can seem quite daunting, but we’ll go through it step-by-step.

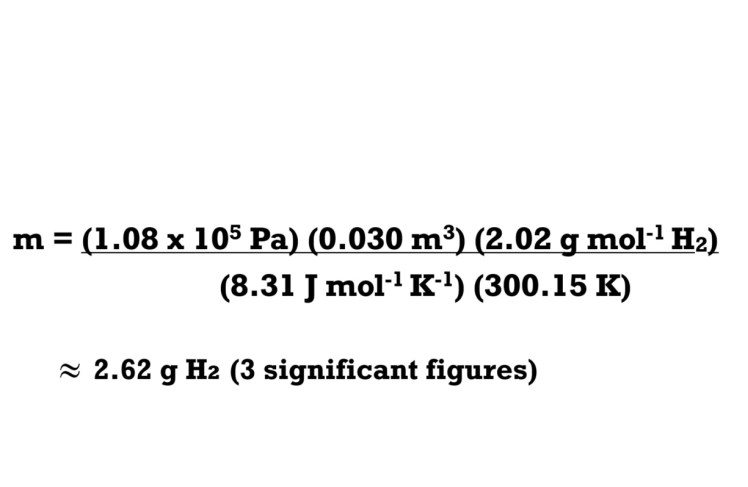

Question: A sample of hydrogen gas (H2) is held within a container with a volume of 30.0 dm3 at a temperature of 27.0oC under a piston at a pressure of 108 kPa. What is the mass of the sample in grams (g)?

Step 1: Convert the temperature from Celsius to Kelvin.

Let’s begin with converting the given temperature to absolute temperature in Kelvin.

Remember: Temperature (K) = Temperature (oC) + 273.15

Step 2: Convert the volume from dm3 to m3.

Next, we can convert our given volume in dm3 into m3 by dividing the given numerical value by 1000.

Step 3: Convert the pressure from kPa to Pa.

Next, we can convert our given value for pressure from kilopascals into pascals. This can be achieved via multiplying the given numerical value for pressure by 1000.

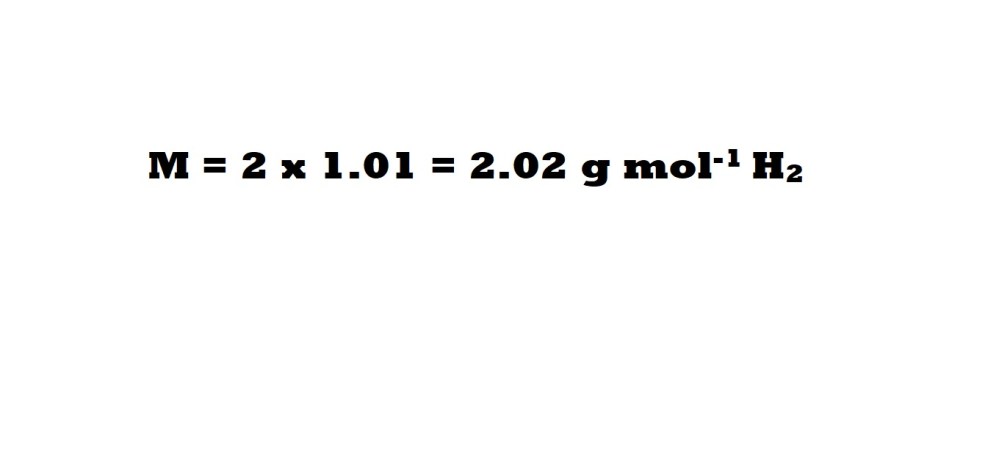

Step 4: Calculate the molar mass of hydrogen gas.

Next, we need to calculate the molar mass of hydrogen gas. Hydrogen gas is one of the elements that exists as a diatomic molecule (a molecule consisting of two atoms of the same element) if it’s not bonded to other elements.

Therefore, the molar mass of hydrogen can be calculated as follows:

Step 5:Plug the variable values and the ideal gas constant for the required unit combination into the modified and rearranged version of the ideal gas equation with mass as the subject.

Therefore, the mass of the sample of hydrogen gas under the piston can be calculated as follows:

Dealing with Molecules Rather than Moles – Boltzmann’s Constant

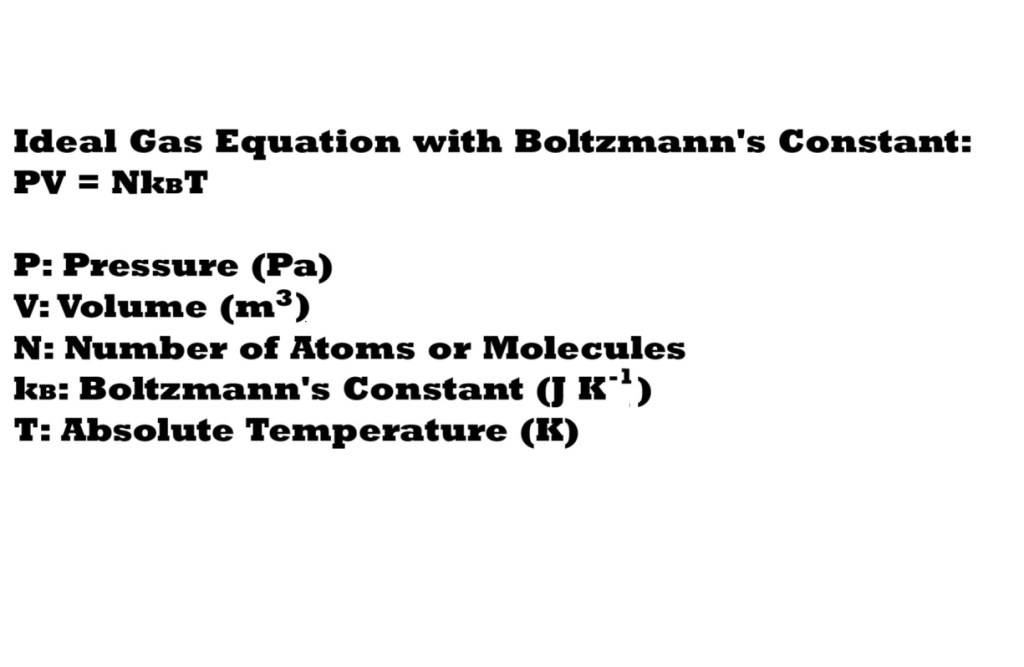

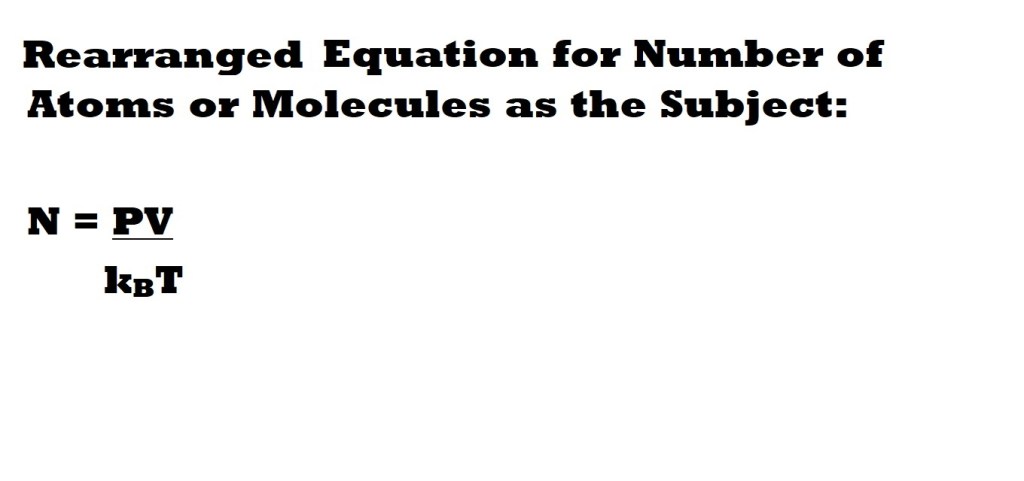

So far we have been dealing with moles of a gaseous substance – however what if we want to consider the actual number of atoms or molecules of a gas present in the system? To do this we have to change the ideal gas equation to include a constant that represents the large number of atoms or molecules of a gas present within a system.

Firstly, let’s remind ourselves how many atoms or molecules there are in 1 mole.

1 mole of any substance contains 6.02 x 1023 mol-1 particles meaning that 1 mole of a gas contains 6.02 x 1023 atoms or molecules. This is known as Avogadro’s number which constitutes Avogadro’s constant (named after Amedeo Carlo Avogadro). This means that if we were to convert the amount in moles into the number of atoms or molecules present by multiplying the amount in moles by Avogadro’s constant we will have a very large number.

If we were to insert the number of atoms or molecules of a gas into the normal ideal gas equation (N) instead of amount in moles we will have two large numbers on one side of the equation: the number of atoms or molecules (N) and the ideal gas constant (R). This would be an issue mathematically as it’s unlikely that we will have equal values on both sides of the equation.

How can we deal with this? We have to insert a really small number into the ideal gas equation to replace the ideal gas constant to ensure a suitable balance with the large number representing the number of atoms or molecules (N) and to ensure the two sides of the equation will be equal to each other.

That really small number is Boltzmann’s constant.

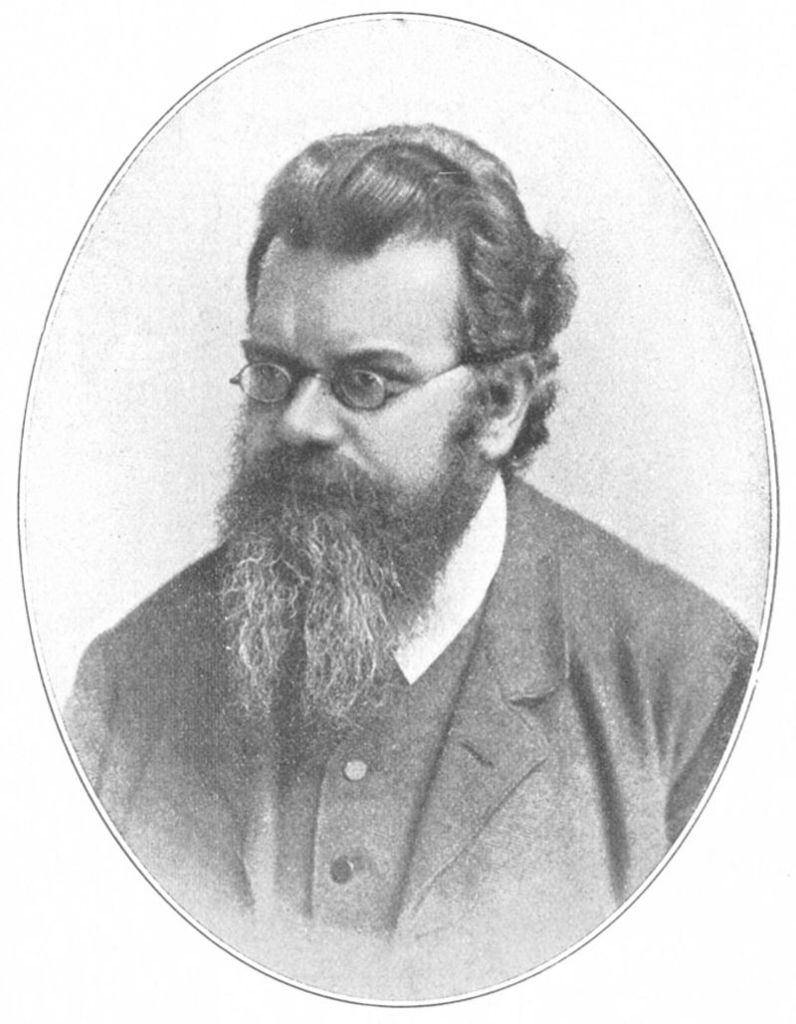

Figure 5: Illustration of Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann (1844 – 1906).

Source of Image: By Lithographie von R. Fenzl – [1][2], Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27805177

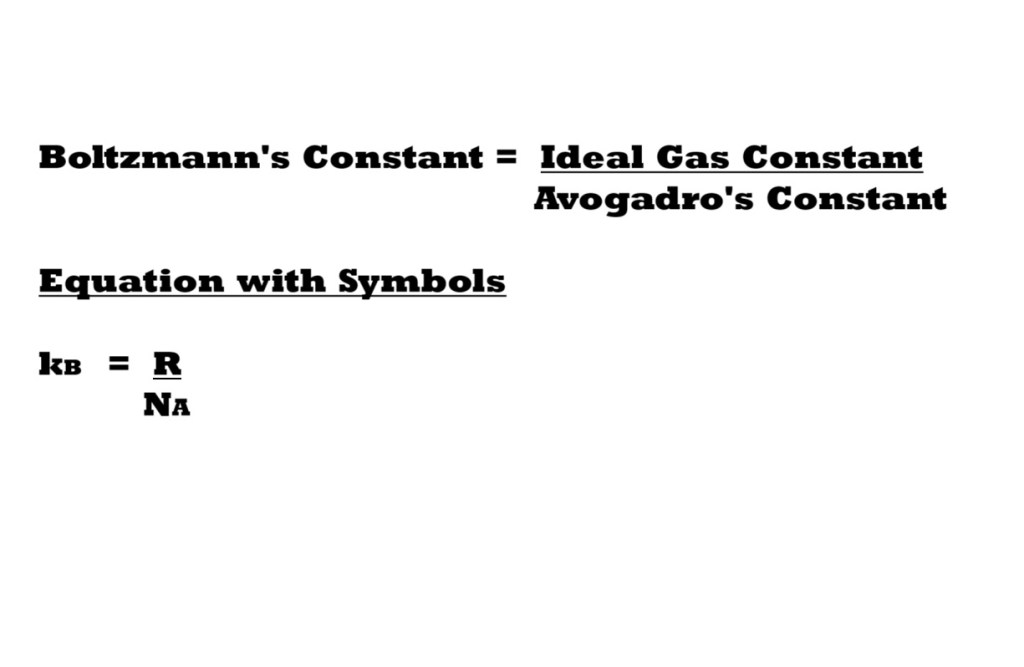

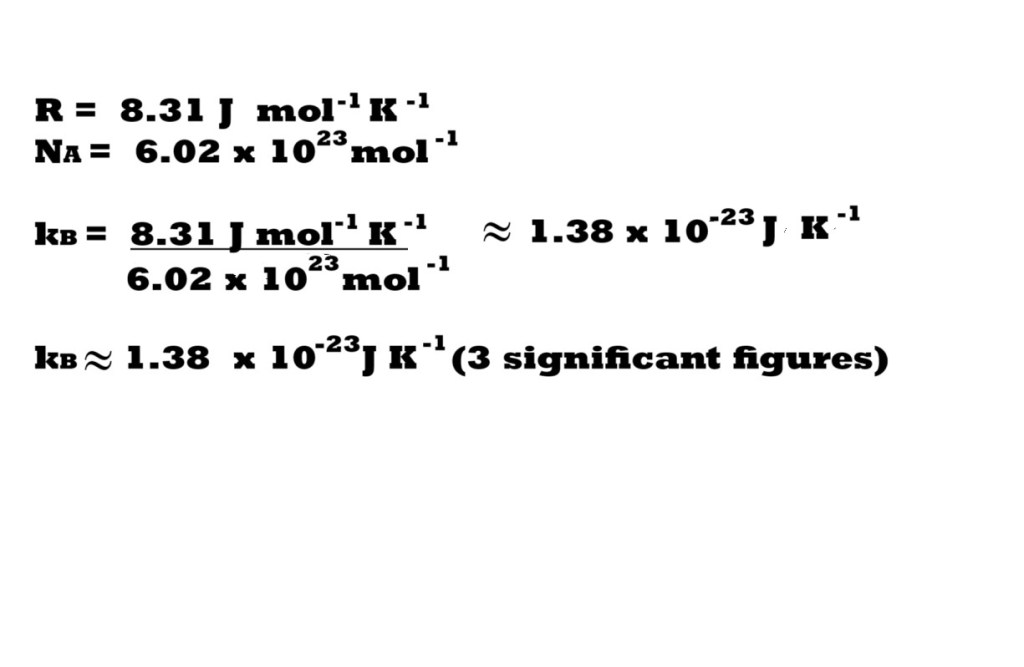

Boltzmann’s constant (named after Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann) can be established mathematically by dividing the ideal gas constant (in J mol-1 K-1) by Avogadro’s constant.

So now we know the numerical value of Boltzmann’s constant we can modify the ideal gas equation to allow us to use it to calculate the number of atoms or molecules of a gas present in a system.

Note: The units included for the other variables correspond with the units within Boltzmann’s constant.

Additional Note: Be wary because the symbol N can also represent Newtons.

Let’s now use the rearranged and modified equation to answer a question.

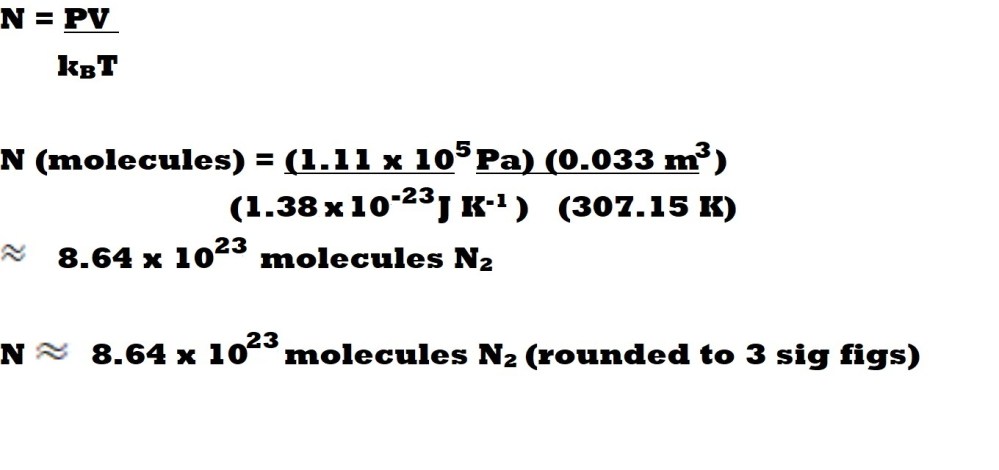

Question: How many molecules of nitrogen gas (N2) are present in a container with a volume of 33.0 dm3, a pressure of 111 kPa and a temperature of 34.0 oC?

Note: Remember to convert the units used for expressing the variables to the same units used to express the constant – which for this question is Boltzmann’s constant expressed in J K-1.

Reminder: Joules (J) represents the units of Pa for pressure and m3 for volume due to the following relationship:

Pa m3 = N m-2 m3 = N m = J

1 Pa = 1 N m– 2 1 N m = 1 J

Let’s go through it step-by-step.

Step 1: Convert the volume from dm3 to m3

To convert from decimetres cubed to metres cubed we need to divide our volume value in decimetres cubed by 1000.

Step 2: Convert the pressure from kPa to Pa.

Next, let’s convert our pressure value from kPa to Pa by multiplying by 1000.

Step 3: Convert the temperature from oC to K.

Reminder: Temperature (K) = Temperature (oC) + 273.15

Step 4: Insert the values for the three variables and Boltzmann’s constant into the rearranged equation and calculate the number of molecules present.

We can now insert the values we have for three variables with the correct units into our rearranged equation with Boltzmann’s constant and calculate the number of molecules of nitrogen gas present in the system.

Problems with the Ideal Gas Law

There are a few situations in which the ideal gas equation wouldn’t be suitable. It wouldn’t be suitable if pressure is exceptionally high as this would cause volume to be very low thereby restricting the movement of gaseous particles (reduced Brownian motion) as there is less space for particles to occupy. This could cause a change in state (conversion to a liquid or solid) as close proximity between molecules could allow for intermolecular forces of attraction between oppositely partially charged regions, thereby drawing the molecules even closer together. Conversely, intermolecular forces of repulsion are also more likely to occur if partially charged regions with the same type of charge (positive to positive and negative to negative) interact with each other in the smaller space.

Also, if temperature is exceptionally low , very low average kinetic energy in gaseous molecules means they move very slowly, thereby increasing the likelihood of molecules interacting with each other and either being drawn together or being repelled from each other via intermolecular forces (collectively known as Van der Waals forces).

Why are the two previous situations so problematic? Here are the two main reasons:

- The ideal gas law does not account for the attraction or repulsion that could exist between gaseous particles and their tendency to be drawn together or to push each other apart. This is due to the assumption that there are no, or negligible, intermolecular forces of attraction or repulsion between gaseous molecules. However, this is usually incorrect for real gases, especially if molecules are close together in a system under high pressure and lack the required average kinetic energy, due to an exceptionally low temperature, to move fast enough to avoid interacting with each other.

- The ideal gas law also doesn’t account for the actual volume occupied by the gas particles themselves– it only accounts for the volume of the container or vessel which the gas could occupy. For example, a container could have a total volume of 45 m3 which would be the value included in the ideal gas equation – however we have no indication about the size of the gas particles and how much volume they actually occupy. The volume of the actual gas particles becomes even more significant when the volume of the container or vessel is reduced under exceptionally high pressure.

So how do we deal with these issues?

How to Deal with a Gas that is too Real to be Ideal

The shortcomings of the ideal gas law can be addressed by a modification to the ideal gas equation that accounts for intermolecular attraction or repulsion and the volume of the particles present.

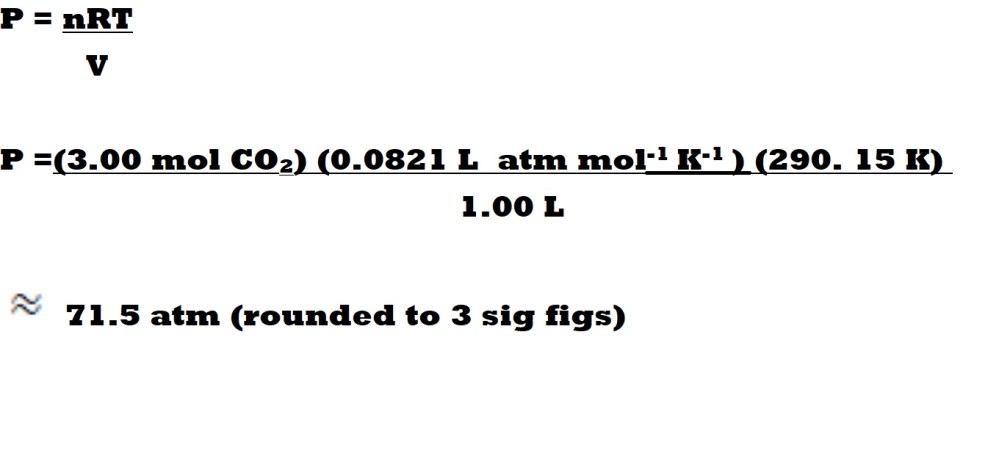

Firstly, let’s take a look once again at the ideal gas equation and conditions involving a real gas in which we have a system (e.g., a container) with a very low volume, meaning it’s likely that a very high pressure will result.

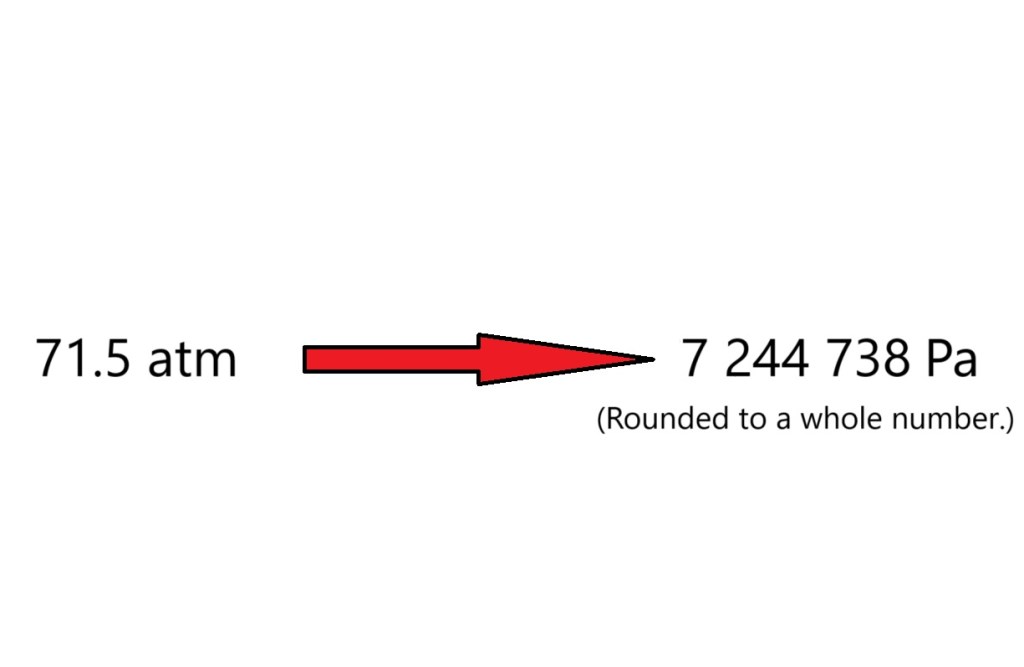

If 3.00 mol of carbon dioxide was present in a container with a volume of 1.00 L and a temperature of 290.15 K, it’s going to lead to an exceptionally high pressure due to the very low volume.

According to the ideal gas equation, this sample of carbon dioxide gas is exerting a pressure of 71.5 atm (to 3 significant figures) which is the equivalent of 7,244, 738 Pa of pressure onto the surfaces of the small container it’s within. That’s quite a lot of pressure.

However, this value may be inaccurate as we haven’t considered how the molecules of the gas may be attracted or repelled from one another, or the volume occupied by the molecules themselves in the small container as the calculation only considers the volume of the small container.

Quick Note About the Type of Van der Waals Force Between Carbon Dioxide Molecules

Carbon dioxide molecules are non-polar meaning they are not going to interact via permanent dipole to permanent dipole interactions. Instead, they will interact via the relatively weaker London dispersion forces in which temporarily induced dipoles between adjacent molecules cause attraction between oppositely partially charged regions. This means that the strength of the intermolecular forces between the carbon dioxide molecules is going to be weaker than the intermolecular forces between polar molecules such as water, however the possible influence of the weak intermolecular forces between the non-polar molecules should still be accounted for.

How can we address this? This is where the Van der Waals equation comes in.

Figure 6: Illustration of Austrian physicist Johannes Diderik Van der Waals (1837 – 1923).

Source of Image: Nobel foundation – http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1910/waals-bio.html, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons,https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6200745

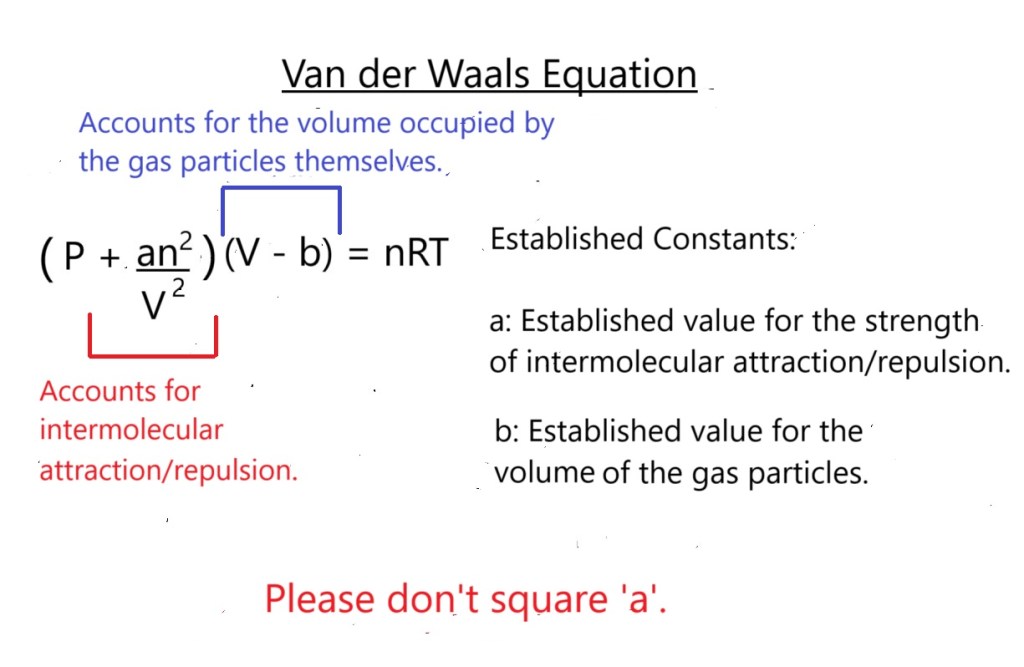

We have already referred to the Austrian physicist Johannes Diderik Van der Waals when referring to the intermolecular forces that can exist between molecules (collectively known as Van der Waals forces). The equation he derived is a modified version of the ideal gas equation that considers the possibility of intermolecular attraction or repulsion and the volume of gaseous particles . This is expressed via two established values that are referred to as established constants or correction factors, which vary according to which gas is involved.

Important Note: ‘An established constant’ is this scenario refers to a value that doesn’t change when examining a specific real gas (e.g., carbon dioxide) in a system where variables such as temperature change. An established constant will be different when examining a different real gas (e.g., hydrogen sulphide).

The equation with included established constants to account for intermolecular attraction/repulsion and the volume occupied by gas particles is illustrated below:

All the other values represent the same constant and variables that are present in the original ideal gas equation.

For an ideal gas, the values for a and b should be 0 because there shouldn’t be intermolecular attraction or repulsion, and the volume of individual particles should be negligible. However, this is often not the case for real gases and each individual gas has its own established values for intermolecular attraction/repulsion and gas particle volume.

Important Note: You will most likely be provided with a list of established values for intermolecular attraction/repulsion and gaseous particle volume for different gases when answering a question using this equation in a test or exam.

Units:

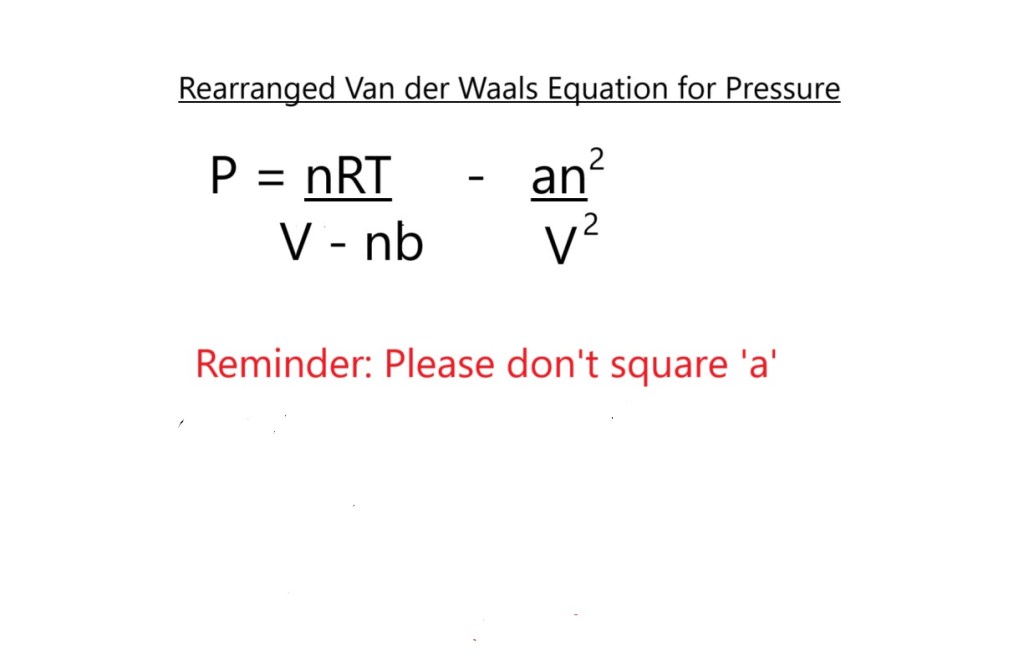

The units conventionally used within the Van der Waals equation are those within Unit Combination 2.

Quick Reminder of the Units in Unit Combination 2:

Pressure (P): atm

Volume (V): L

Amount in Moles (n): mol

Temperature (T): K

Ideal Gas Constant (R):

L. atm or atm. L

mol. K mol. K

a: Strength of Intermolecular Attraction/Repulsion ( atm L2 mol-2 )

Established constant ‘a’ or correction factor ‘a’ accounts for intermolecular attraction or repulsion, therefore it must contain the units used to express pressure, the volume of the system and the amount in moles.

‘b’: Volume of the Gas Particles ( L mol-1 )

Established constant ‘b’ or correction factor ‘b’ considers the volume (size) of the gas particles, therefore it must contain the units used to express the volume of the system and the amount in moles.

Let’s now rearrange the van der Waals equation to allow us to use it to calculate the pressure exerted by our sample of CO2 and let’s see if the value differs to the one we had from the ideal gas equation.

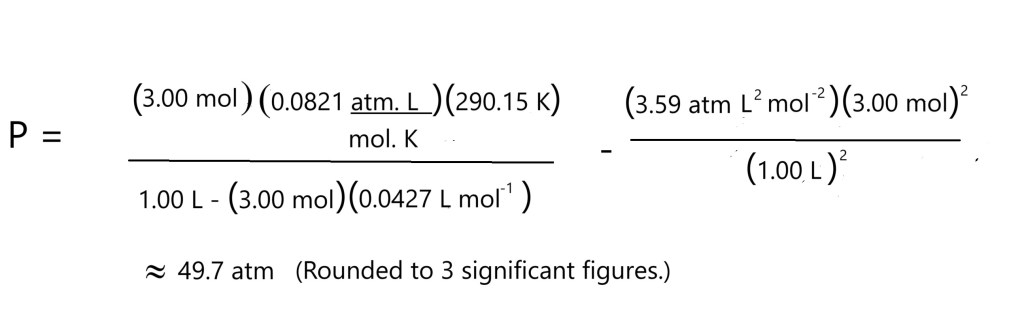

The established constants or correction factors for carbon dioxide are as follows:

a: 3.59 atm L2 mol – 2

(This accounts for the possible intermolecular attraction stemmed from the weak London dispersion forces caused by temporarily induced dipoles.)

b: 0.0427 L mol-1

Let’s compare the values we have from the two equations:

Ideal Gas Equation:

P: 71.5 atm or 7 244 738 Pa

Van der Waals Equation:

P: 49.7 atm or 5 035 853 Pa

A significant difference of 21.8 atm or 2 208 885 Pa is evident between the values for pressure from the two equations. This illustrates how unreliable the ideal gas equation can be when examining a real gas at a high pressure. The value from the Van der Waals equation is more likely to be accurate as it considers intermolecular attraction or repulsion and the volume occupied by the molecules themselves.

Conclusion

The ideal gas law – in theory – should be the perfect way of examining gases as it encompasses all the main properties and combines the principles identified by the four main laws on gas behaviour. However, we have seen how real gases don’t always comply with the ideal gas law and that the equation needed to be modified to allow it be more suitable for gases in various conditions.

We’ve reached the end of this tutorial and this series on gas stoichiometry.

I hope you found this series of tutorials helpful.

Bye for now.

References

- Webster, C (1965). ‘The Discovery of Boyle’s Law and the Concept of the Elasticity of Air in the Seventeenth Century.’ Archive for History of Exact Sciences. Springer-Verlag. 2, 441 -502. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00324880

Non-original images are attributed to original authors.