When I studied chemistry in college I used to go home and talk to my grandfather (who’s an engineer) about what I had learned that day. However, when it came to the mole, I found myself pausing mid- sentence to mentally check to see if every detail was correct; this was because it seemed like whenever I thought I remembered everything about this deceptively tricky topic – there was a minute detail that could prove costly if omitted or misunderstood in an exam.

So, in this post I’m going to be running through what the mole is; why we use it as a measurement; how to calculate the amount of a substance in moles and how it relates to mass – plus the number known as Avogadro’s number.

What is the mole?

The mole is an SI unit that expresses a measurement of the amount of a substance (which could consist of atoms, molecules or ions). The first thing to note is that when we say ‘amount’ we don’t mean the same thing as ‘mass’. The amount of a substance refers to the number of particles – whether that’s atoms, ions or molecules – present in a sample, whereas the mass is a measurement of how heavy a sample of a substance is.

So for instance if we have 50g of magnesium chloride, that means that we have a sample of magnesium chloride that has a mass of 50g, but the amount of the substance present would be a measurement of the number of ions of magnesium and chloride present in the sample.

Or – for a slightly more tasty analogy – if you had a piece of Victoria sponge cake (illustrated below) and that piece of cake contained 40g of sucrose (table sugar), the mass would be 40g, but the amount as expressed in moles would refer to the number of sucrose molecules present in the cake.

I actually made the cake pictured and I may have thought about the number of moles present – but then realised I only had about 20 minutes to make it for a party, so mole calculations had to be put on hold.

Okay, let’s now delve into the portion of this topic that caused myself and my college peers a bit of a headache when we were first introduced to it . I’m referring to Avogadro’s Number.

Avogadro’s Number/Avogadro’s Constant

6.02 x 10 23

The number above is crucial in the world of the mole. This number indicates how many particles are present in 1 mole of a substance.

Let’s briefly explore that number.

It is written in standard form or scientific notation, which is a way of expressing either a really small number or a very large number – and in this example it’s a very large number. (I won’t go into too much detail about standard form in this post – but please leave a comment if you want me to produce a tutorial on standard form.)

The number if written out using the decimal numeral system would look like this:

602 000 000 000 000 000 000 000

This is 602 hexillion and if we were to write it out in decimal form every time we had a mole of something, it would take up quite a lot of time and paper. So, instead we express it as a multiplier in 3 significant figures of 6.02 followed by a multiplication sign and a base of 10 to the power of 23.

However, if you were to type into a search engine the phrase ‘Avogadro’s number’ you would get a number beginning with 6.02, but then various other numbers before you get to the multiplication sign. This is the true value of Avogadro’s number, however we round the number to 3 significant figures, as is common practice in chemistry – which we will see when we do some calculations in a bit.

(It’s a similar situation to pi – not pie the edible product- which is expressed as 3.14, rather than writing more of the infinitesimal number of figures.)

Avogadro’s Number was named after an Italian physicist named Amedeo Carlo Avogadro. Avogadro was known for his work on the behaviour of molecules of gases at different temperatures and pressures and devised Avogadro’s law. (I’ll discuss Avogadro’s law in another post.)

But why is Avogadro’s number part of a principle known as Avogadro’s constant? It’s because one mole of a substance – no matter what that substance is – contains the same number of particles as there are atoms in 12g of the Carbon-12 isotope – which is 6.02 x1023. (We’ll get to Carbon-12 in a bit.)

So, let’s say we have 1 mole of carbon dioxide (CO2) molecules, in that sample we will have 6.02 x 10 23 molecules of carbon dioxide.

Alternatively, for the sake of dietary balance because we used cake as an example earlier on, if we had 1 mole of apples we would have 6.02 x 10 23 apples – which would probably be enough to run a pretty successful cider business.

Anyway, the point is that whenever you have 1 mole of anything, you have 6.02 x 1023 particles of that substance – hence the phrase Avogadro’s Constant.

Why do we measure in moles?

The main reason why the mole is used as a measurement in chemistry is because it provides an internationally recognised practical way of calculating and recording the amount of a chemical substance.

If the mole wasn’t used as a measurement, there wouldn’t be a pragmatic way of measuring and recording the amount of a substance; for instance, if we wanted to note the amount of water we needed as a reactant, it would be practically impossible to count 6.02 x 1023 molecules of water. (Multiple generations of people would have to dedicate themselves to the cause and you would need a means of seeing the diminutively sized molecules.) So, the mole tends to do a lot of the work for us.

Okay, now we have to address how mass influences the calculation of the amount of a substance in moles

I’m going to use a definition of a mole that you will see written in textbooks and you’ll need to remember for exams.

One mole of a substance contains the same number of particles as there are atoms present in 12g of Carbon-12.

What this statement refers to is that when you calculate the number of moles of Carbon-12 atoms present in a 12g sample of Carbon-12, the answer will be 1 mole.

Let’s see how that comes about.

Calculating the Number of Moles Present using Mass

Okay, the word ‘mass’ is going to be used in this section within four definitions that are crucial to know – but I’ll explain them within a table to make it a bit easier to explain.

Okay (deep breath), the definitions will be of Relative Atomic Mass; Relative Isotopic Mass; Relative Formula Mass and Molar Mass.

| Variable | Definition |

| Relative Atomic Mass | The average mass of an atom of an element (considering all of its isotopes and abundances) compared to 1/12 of the mass of one atom of Carbon-12. No units. |

| Relative Isotopic Mass | The mass of one atom of an isotope of an element compared to 1/12 of the mass of one atom of Carbon-12. No units. |

| Relative Formula Mass | The sum of the relative atomic masses of the atoms/ions present in a compound. No units. |

| Molar Mass | The mass of one mole of a substance. Given in the units of g mol-1. |

I won’t go through a relative atomic mass calculation in this post, but if you want me to go through the process in another post please leave a comment.

The term ‘isotope’ refers to an atom of an element that has a different number of neutrons present in its nucleus than other atoms of that element – but has the same number of protons and electrons as other atoms of that element (indicated by its atomic number).

The relative isotopic mass of each isotope of a particular element plays a crucial role in the calculation of the relative atomic mass of an element. In order for relative atomic mass to be calculated, we must consider the relative isotopic masses of all isotopes of an element and the abundance (expressed as a percentage figure) of each isotope.

The value of the relative atomic mass of an atom of each element (which is usually rounded to three or four significant figures) is expressed in the periodic table.

The reason the mass of 1/12 of the mass of an atom of Carbon-12 is referred to as a comparison for both relative atomic mass and relative isotopic mass is because it is equal to the mass of an atomic mass unit.

An atomic mass unit (amu) is a unit of measurement which is used to express how heavy an atom is rather than using grams. (I know, it’s another awkward little detail in this topic – but it’s for a good reason.)

The mass of atoms are pretty difficult to figure out accurately. The most accurate way of figuring out the mass of individual atoms of different elements, is to compare atoms of all elements to a particular atom – which is Carbon-12 (the most abundant isotope of Carbon).

(This is why Carbon-12 is spoken about so much; it acts like a benchmark when considering the mass of all other atoms.)

In addition to relative formula mass, you may also see or hear the phrase ‘relative molecular mass’. This is the sum of the relative atomic masses of atoms present in a molecule – but it does not refer to ionic compounds, whereas relative formula mass can be used to refer to both molecules/covalent compounds and ionic compounds.

So let’s prove that 12g of Carbon-12 contains 1 mole of Carbon-12 atoms. To do that we need the formula for working out the number of moles present.

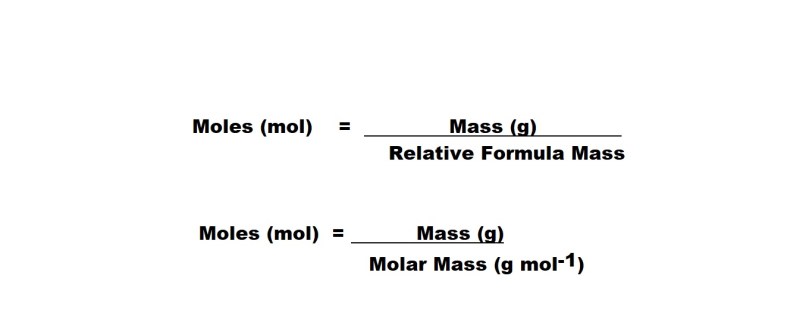

I know – there’s two formulas rather than one; there is a good reason for this. Some exams will allow you to calculate the amount of a substance in moles using relative formula mass – however in other exams you could be asked to define molar mass and then use that as a variable in calculating the number of moles.

I would advise that you ask your teacher or lecturer whether to use relative formula mass or molar mass for your upcoming exams.

I’m going to show you how to use both relative formula mass and molar mass in a calculation.

Note: The calculations featured in this tutorial will not involve the use of conversion factors. I will write a separate accompanying piece featuring calculations involving the use of conversion factors.

Note: You will need a copy of the periodic table to perform mole calculations.

Note: You should round your answer to the same number of significant figures as there are in the value of the variable with the fewest significant figures in the question.

Example of a Mole Calculation using Carbon-12

Using Relative Formula Mass

Mass of Carbon-12 = 12.0g

Mr = 12.0

12.0g / 12.0 = 1.00 mol

Using Molar Mass

Mass of Carbon-12 = 12.0g

M = 12.0 g mol -1

12.0g / 12.0 g mol -1 = 1.00 mol

Key

Mr: Relative Formula Mass

M: Molar Mass

You can see in the above calculation that the relative formula mass and molar mass are equal in numerical value, yet they differ in meaning and in the presence of units. However, using both formulas, we have proven that one mole of Carbon-12 atoms are present in 12g of Carbon -12.

Note how the mass of the sample of Carbon-12 and the relative formula mass/molar mass are equal. This would be the case if we were to have a sample of atoms of an element that was the same mass as the atom’s relative atomic mass – which would mean 1 mole of atoms of that element would be present. This is why it says in textbooks that the relative atomic mass in grams of any element contains one mole of atoms.

Also note that because we only have a sample containing atoms of the Carbon-12 isotope, the relative formula mass and molar mass are equal to the relative isotopic mass of Carbon-12 which is 12.0.

Let’s do one more calculation with another substance before we move on to the final section. (We’re nearly there.)

Example of a Mole Calculation using Methane (CH4 )

Using Relative Formula Mass

Mass of CH4 = 3.00g

Mr = 12.0 + (4) (1.01) = 16.04

3.00 g / 16.04 = 0.187 mol

Using Molar Mass

Mass of CH4 = 3.00g

M = 12.0 g mol -1 + (4) (1.01 g mol -1 ) = 16.04 g mol-1

3.00g /16.04 g mol -1 = 0.187 mol

Both the relative formula mass and molar mass in the above calculation were calculated by adding up the relative atomic masses of 1 carbon atom and 4 hydrogen atoms – as indicated in the periodic table.

Note: The number of moles present is expressed in 3 significant figures in the above calculation.

Okay, so now we know what the mole is and how to calculate the amount of a substance in moles. But what if we knew the amount of a substance in moles, but we wanted to know its mass.

Calculating Mass using Moles

Let’s pretend that our lab’s scales are broken and there isn’t another one available for a really important experiment. We know how many moles of a substance we have, but we want to know its mass. What are we going to do? Well, we just have to do a bit of rearranging of a formula we already know.

Mass (g) = Moles (mol) x Relative Formula Mass

Mass (g) = Moles (mol) x Molar Mass (g mol-1)

Once again I’m covering a formula involving relative formula mass and one involving molar mass.

If we wanted to know the mass of a substance, we would just have to make mass the subject (the variable that’s going to be worked out) of the formula. This would involve multiplying the amount of a substance in moles by the substance’s relative formula mass or molar mass. Let’s have an example.

Example of a Mass Calculation using Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

Using Relative Formula Mass

Amount in Moles (mol) = 1.50 mol

Mr = 12.0 + (2) (16.0) = 44.0

(1.50 mol) (44.0) = 66.0 g

Using Molar Mass

Amount in Moles (mol) = 1.50 mol

M = 12.0 g mol -1 + (2) (16.0 g mol -1 ) = 44.0 g mol -1

(1.50 mol) (44.0 g mol -1 ) = 66.0 g

Key

Mr: Relative Formula Mass

M: Molar Mass

Note: The mass of carbon dioxide is expressed in 3 significant figures.

Finished!!!

We have reached the end of this first tutorial (cue sighs of relief). When my college peers and I finally understood the mole, we felt more confident about going forward not only in chemistry but in the other sciences too. Learning about the mole and how it relates to mass involves understanding many small but crucial details. However, once you’ve learned about the mole – learning everything else seems more possible.

In the next tutorial, we’ll go through how to convert between a measurement of the amount of a substance in particles to a measurement expressed in moles and vice-versa using Avogadro’s number.

Bye for now.

All images featured in this post are my own.